The United Nations Environment Programme and the World Wildlife Fund released separate reports this week — ahead of the next round of global plastics treaty negotiations slated to begin at the end of this month — that highlight extended producer responsibility for packaging and promote reuse systems and elimination of certain single-use plastics as among the key design and regulatory solutions for curbing plastic pollution.

The UN last year initiated the treaty development process, which is anticipated to run through 2024. It aims to include technical provisions that consider how to promote “sustainable” plastics production and consumption across their life cycle in a way that’s feasible for stakeholders around the globe, the executive secretary of the intergovernmental negotiating committee said earlier this year. Draft treaty text is expected later this year.

On Monday, WWF released a set of reports developed by Eunomia, a consulting firm with expertise in waste management, that are focused on regulating high-risk plastic products. WWF described eliminating high-risk and unnecessary single-use plastics as “the first step towards creating a fairer and more circular economy.”

Consumer packaging ought to be a main focus are for the treaty, due to the widespread volumes of low-value, lightweight and disposable items that contribute to pollution risk, said John Duncan, global initiative lead for No Plastic in Nature with WWF International, via email. “Control measures in the treaty must be binding and tailored to eliminate the pollution risks of each particular plastic packaging type,” Duncan stated.

Packaging is a “complex and high-risk category,” WWF noted, pointing to data indicating that packaging accounts for about 31% of all global plastics use. The news release also stated that for plastics that can’t be easily eliminated, minimum requirements on recycled content, reuse systems and deposit return schemes can all play a role. Criteria tests for packaging necessity and EPR should be applied for all plastic packaging, Duncan said.

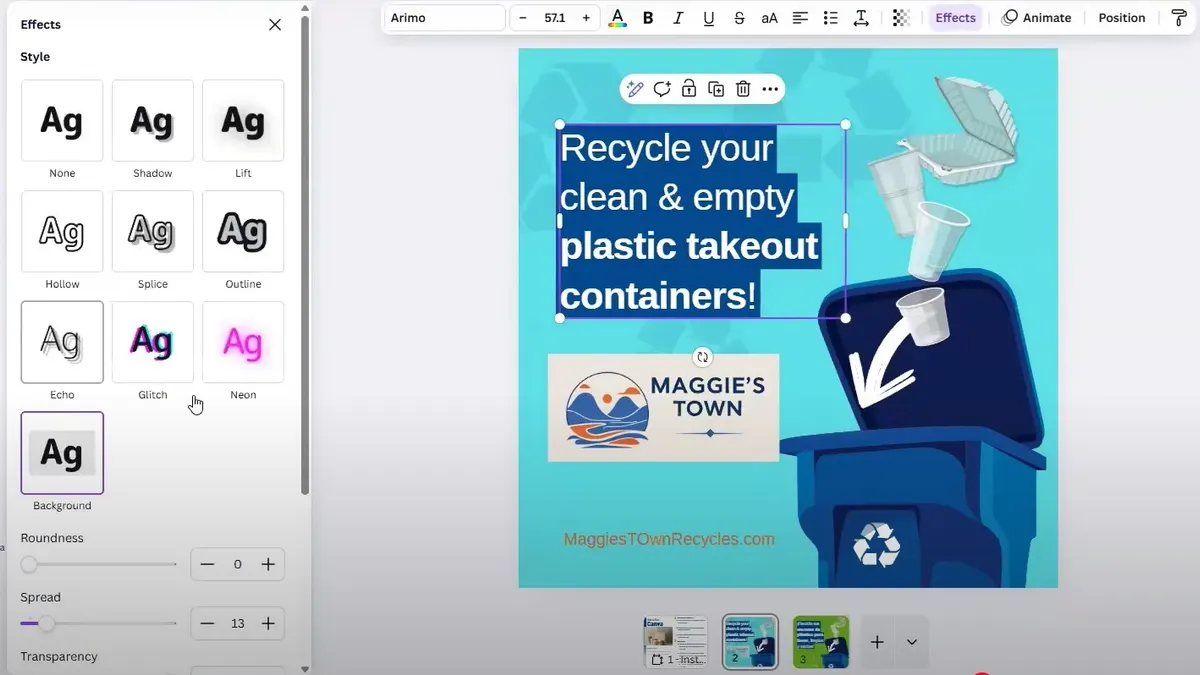

The organization said that, upon adoption of the treaty, it’s calling for bans on plastic items such as single-use cutlery, plates and cups. WWF also said that if immediate bans on single-use food and drinks packaging aren’t feasible, the treaty should instigate phase-outs by 2035 and introduce product standards and economic measures that decrease demand to reduce plastic use.

Packaging industry stakeholders have engaged on the issue of “problematic” plastics in recent years through groups like the U.S. Plastics Pact, which last year released a list of 11 plastic packaging items it deemed important to phase out in the next few years, given their limited potential for reuse, recycling or composting in the U.S. WWF’s latest reports were informed by those types of frameworks, Duncan said, but its own analysis further considers the global prevalence and transboundary risks of pollution caused by certain plastic product groups.

UNEP’s own “Turning off the Tap” report — financially supported by the governments of Norway and Sweden and authored by representatives from UNEP, climate and systems change-focused firm Systemiq, and the University of Portsmouth in England — was released Tuesday.

It describes how a combination of reducing “problematic and unnecessary plastic use” and improving recycling and reuse systems could enable an 80% reduction to plastic pollution by 2040, pending nations and industry making “deep policy and market shifts using existing technologies.” The “careful replacement” of plastic wrappers, sachets and takeaway items with products made from alternatives like paper or compostable materials alone could account for a 17% decrease, the report found.

“The highest costs in both a throwaway and circular economy are operational,” UNEP said. “With regulation to ensure plastics are designed to be circular, [EPR] schemes can cover these operational costs of ensuring the system’s circularity through requiring producers to finance the collection, recycling and responsible end-of-life disposal of plastic products.” Standards could also be created to hold manufacturers responsible for products that shed microplastics.

With EPR, fragmented national approaches — including different types of plastics regulated and varying fee structures — are hurting progress globally, the report said. “Shared guidelines and minimum standards for EPR are necessary to define the desirable necessary minimum operating standards of EPR schemes,” the UN stated.

UN authors noted that while systemic change requires huge investment, funding could come from shifting planned investments from new production facilities or by placing a levy on virgin plastic production.

The UN report also drew criticism from various environmental groups. The Center for International Environmental Law decried limited observer participation in the upcoming negotiation session, and the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives opposed the inclusion of burning plastic waste.