A year and a half after WM reopened the doors at its upgraded MRF in Germantown, Wisconsin, visitors can spot a specific material being pulled from conveyors and baled for sale that isn't at many other U.S. MRFs: plastic film.

WM primarily intended for the $39 million in upgrades at the facility — which is roughly 15 miles northwest of downtown Milwaukee — to increase capacity and reduce contamination. Since reopening in January 2024, Germantown now can process upward of 230,000 tons of material annually, a more than 50% increase from before. WM forecasts that its recycling volumes will continue to grow in the region as population increases and as recycling participation ticks up.

Notably, the Germantown site now features a film extraction system, said Troy Hanson, director of operations at the Germantown MRF. Plastic bags and other films still aren't accepted curbside, and removing them offers the benefit of reducing contamination in other material streams.

But WM is also testing this material's viability as a commodity instead of just considering it a tangler.

“We continue to get a lot of plastic bags and a lot of film-type materials in the material stream, so there's the benefit of extracting that film out — to try to capture that film and to sell that film,” Hanson said. That being said, it “is difficult because there's not a lot of end markets for it.”

WM announced in 2022 that it would launch a pilot program for curbside recycling of film. The initial program was in a Chicago suburb, and the material headed to the company’s nearby “MRF of the future.” WM said at that time that it planned to invest $800 million through this year to enhance other facilities to process film and other newer accepted materials.

This spring, WM unveiled a new $150 million Natura PCR plastic film recycling facility in Waller, Texas. Natura PCR became an independent entity in 2022 when WM acquired a controlling stake in Avangard Innovative.

The Germantown upgrades also improve the MRF's capability to capture more plastic No. 4 and No. 5 tubs and lids, said John Schultz, recycling facility manager at the MRF. “Previously, we had been dealing with fives, but the old technology struggled with the fours because it couldn't tell the difference between a lid and a plastic bag,” he said.

Those enhancements came into play when nearby Waukesha County announced in May that it selected WM as its new recycling processor. The county noted that the 100,000 households within its service now can recycle curbside their No. 4 plastics, LDPE containers like yogurt tubs, instead of disposing of them.

WM partners with Alabama-based KW Plastics to take its No. 4 and No. 5 plastics to recycle and incorporate into products like tubs and buckets. But a lot of the material recovered at the Germantown MRF stays within Wisconsin for further processing into new products and packaging. For example, a large proportion of the OCC stays local and is made into new boxes, while other paper grades that remain in Wisconsin become tissue products such as paper towels, Schultz said.

The new system also is flexible and able to be expanded. This helps to future-proof the facility as new packaging is developed, collected curbside and travels through the MRF, Hanson said.

“We certainly anticipate that material types are going to continue to evolve,” he said. “We wanted to enable ourselves with technology that will help us be able to adapt when we need to to capture those materials — if there's end markets for some of the materials — that are going to be part of that evolution.”

Equipment and skills upgrades

The Germantown upgrades are part of WM’s plan to invest $1.4 billion from 2022 to 2026 to update existing facilities and build new ones across North America. The company has made a push to enhance automation at its facilities, which increases efficiencies and reduces dependence on manual labor.

The principal reason for the Germantown retrofits was to leverage technology to improve operations and efficiencies, Hanson said. But an ancillary benefit is to reduce challenges related to hiring and retaining workers for “physically intense” sorting jobs.

“It was just becoming increasingly difficult to staff the plant,” he said. “With the old system, we were largely reliant on people hand-sorting the materials. Now we're largely relying on technology.”

With machines now performing more of the physically demanding tasks, WM upskilled many of the employees it retained. Before the facility retrofit was complete, the company began in-depth training for employees to learn about the new system components.

"We have more technicians, and we have more people on the lines that are really managing the system, [rather] than just physically sorting the materials," Hanson said.

But the upskilling started prior to that, Schultz said, referencing demolition of the old equipment and build-out of the new.

“We had people that were on the line that learned to use a torch, and they were cutting up conveyor belts and things. And as we were building, they were here with the vendors and the contractors helping to install,” he said. “They got a firsthand look at the equipment as it's going in. We got a lot of buy-in, because they helped build this place.”

He emphasized that soliciting and incorporating employee suggestions into plant equipment and operations not only ensures they're invested in their work and place of employment, it also results in the “double win” of “significant improvements” at the facility. Input from Germantown employees has helped WM boost safety and efficiency in addition to material recovery and quality, Schultz said.

The balers and the baler feed lines are largely the only equipment left from the previous system, he said, and everything else is brand new. Germantown now has 17 optical sorters, up from the previous four. It also has ballistic separators and air separation systems.

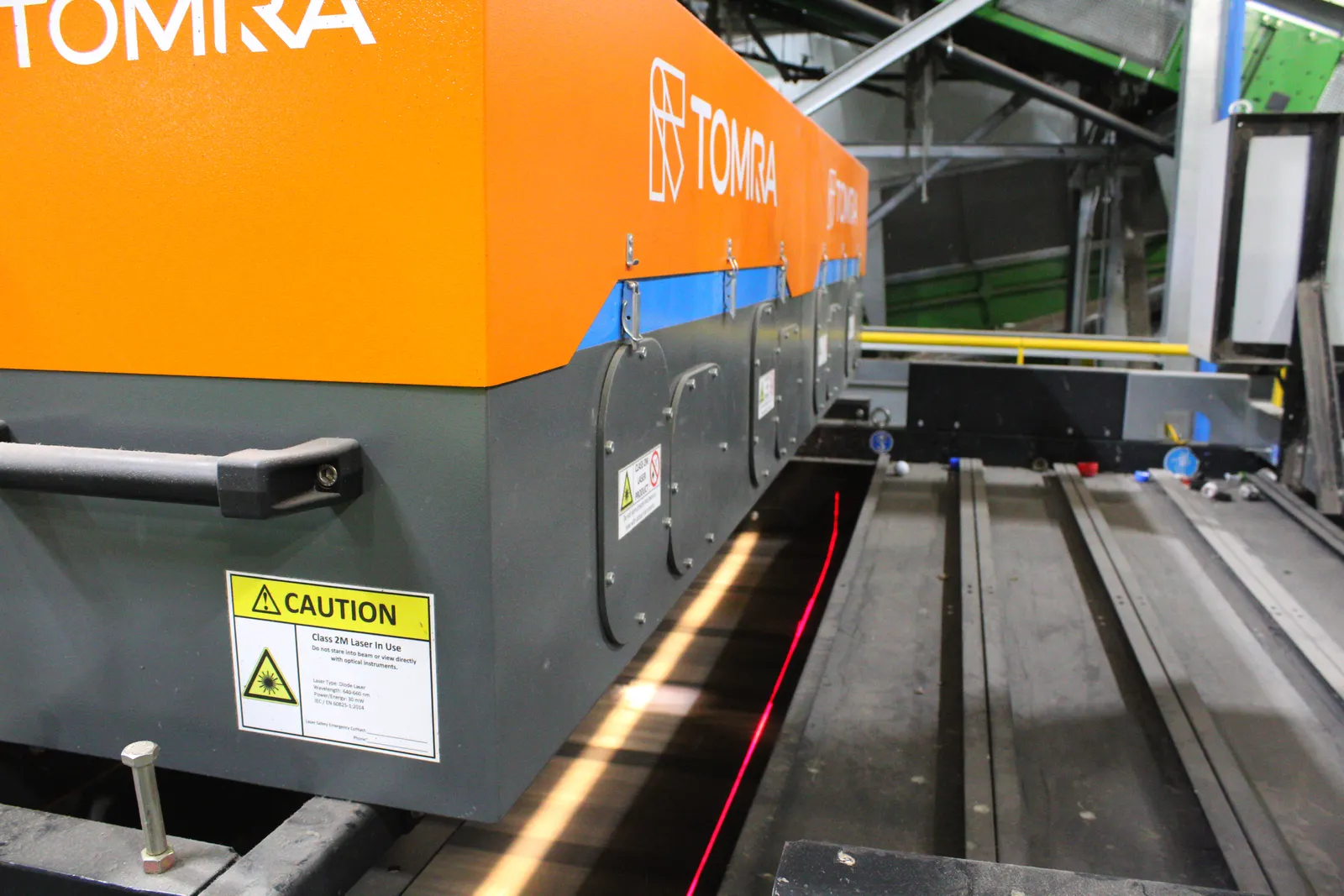

The optical sorters’ white lights and cameras make the first determination of a material type based on its reflection. This is a dependable way to detect paper and plastics, Schultz said, “but one of the drawbacks is water bottles and aluminum cans look the same. So we have that metal detector so it can distinguish [them].”

These optical sorters also have a new feature, red laser beams, that allows for detection of black plastics. “A black tray on a black rubber belt looks the same. But by having the laser that's detecting height, it can detect that there is a black tray there and sort it. So now we're able to recover black polypropylene,” Schultz said.

The film extraction station is one area where humans are still positioned along the line. When workers encounter a plastic bag or another viable film on the fiber conveyor, they pick it and raise it to an overhead tube that sucks it up and transports it to a collection location.

Cutting contamination and improving safety

Reducing contamination while boosting processing capacity were two of the key drivers for retrofitting Germantown. Lithium-ion batteries are the top contaminant with the greatest risk, Hanson said, which prompted WM to focus on safety and fire system upgrades, too.

“The thing that keeps me up at night is the batteries and the risk of fires,” he said, while describing the newly installed Fire Rover system at the MRF.

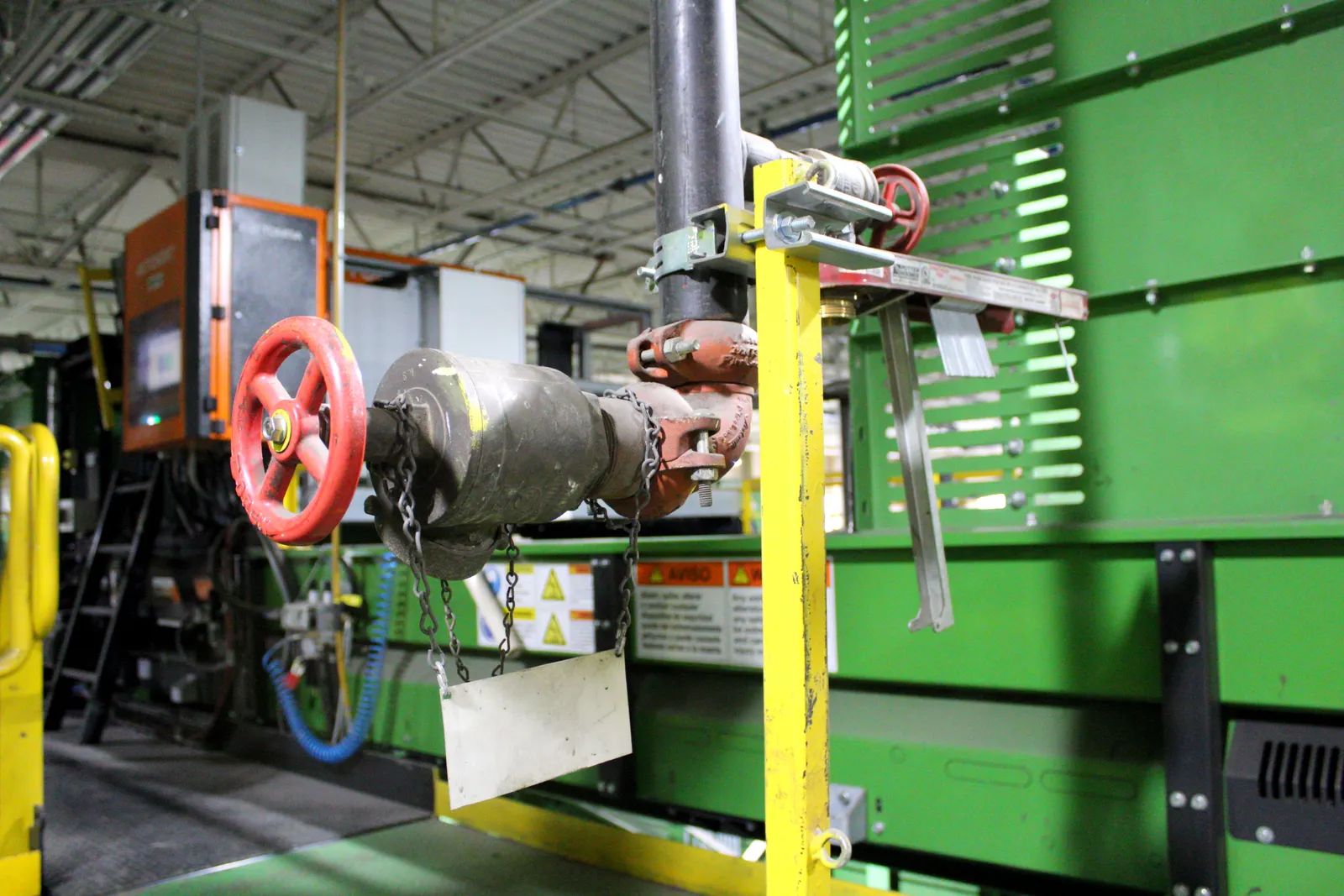

WM also collaborated with the Germantown Fire Department while designing the MRF, according to Schultz. That prompted the company to install fire safety features such as a stand pipe inside the facility, which provides firefighters much easier access to water than bringing in hundreds or thousands of feet of hose from an outdoor hydrant.

The air separator technology also aids with identifying batteries, and a worker manually pulls batteries off the line. The plant has a collection area for larger e-waste that's manually pulled.

Pointing to the numerous clothing items circulating on conveyors, Schultz says that's also technically contamination. But some of it initially appears in the recovery line due to a feature of the new technology.

More textiles are being manufactured from recycled PET bottles, and the new MRF equipment recognizes the plastic in the clothing as PET. But that material must be separated from the other PET bales and sent to a textile recycler or for disposal, because WM's customers want blow-molded PET, Schultz explained.

Education element

Recyclers consistently work on consumer education, especially when entering a new region or handling additional types of materials. The desire to provide education is why WM opened up the Germantown facility for a select number of tours in participation with the Association of Plastics Recyclers’ nationwide MRF tour initiative this spring.

“We think about education with residents or our customers, and we think about that with the organizations that we partner with,” said Taryn Nance, WM area communications manager for the Upper Midwest.

The Germantown MRF is WM’s only residential single-stream facility in Wisconsin, and it draws material from much of the state in addition to part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Beyond educating about recycling in these specific communities, WM aims to spread knowledge about recycling in general.

“Something that we've seen as a company is that there's kind of a myth out there still, among a lot of people, that recycling isn't real,” Nance said. “It is, in fact, real, which is one of the reasons we wanted to invite people into the facility to check it out.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to clarify the nature of WM's recent agreement with Waukesha County.