Industry experts say landfill operators should anticipate new regulations targeting per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) on the state level in coming years. Those fast-unfolding changes, impacting groundwater and surface water, come alongside emerging research as more becomes known about PFAS in landfill gas.

During a session at this year's virtual WasteExpo devoted to going "beyond the basics" of PFAS, speakers said following the trajectory of policy is key for industry players facing an increasingly varied national regulatory landscape.

"Regulations across the country are changing day to day, moment to moment. [It's a] race to the bottom as each state adopts standards that seem to be lower and lower," said Nikki Delude Roy, vice president for environmental consulting firm GeoInsight, referencing the levels of PFAS states are permitting in water.

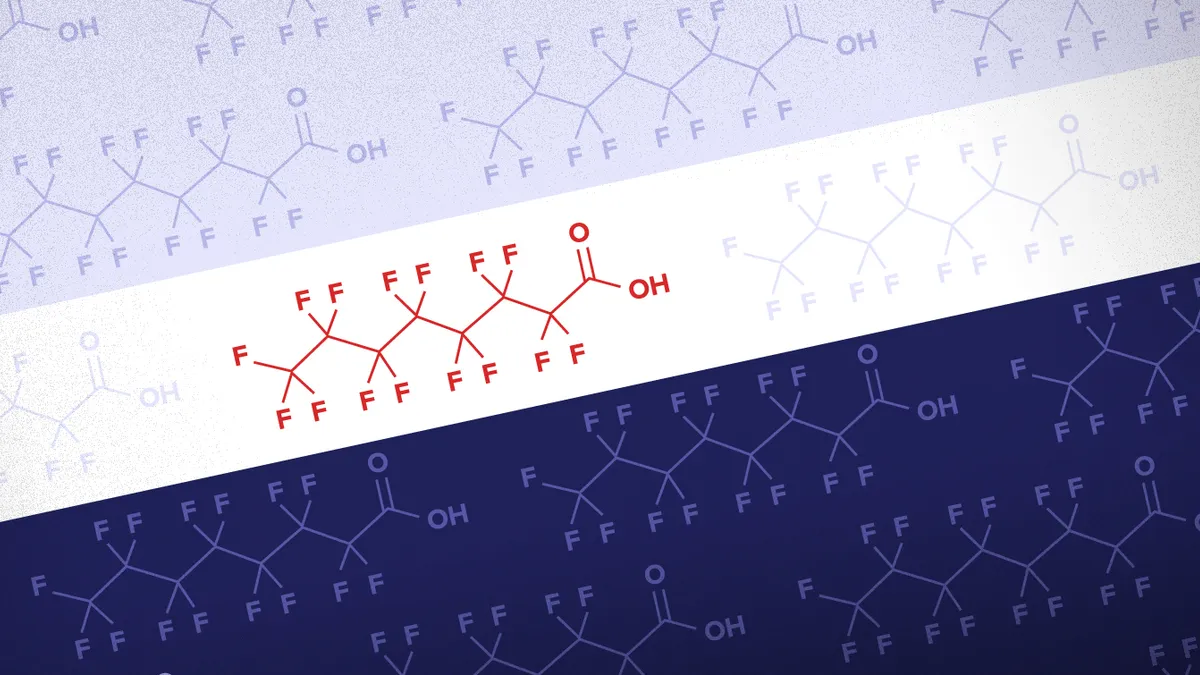

There are over 4,500 types of PFAS, chemicals known for their non-stick properties. Several, including the more well-known PFOS and PFOA, have been repeatedly linked to health effects like cancer and developmental issues by the U.S. EPA.

Those established impacts have led to a regulatory push. Drinking water has been a primary point of concern, as consumption through water or food is likely the leading source of PFAS in people. EPA has an advisory level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOS and PFOA, but the agency has not made that mandatory through a maximum contaminant level (MCL) despite calls from environmental groups and some lawmakers.

States have moved much more quickly, Roy said, resulting in a disjointed series of regulations and proposals across the country. "It's becoming an incredibly challenging regulatory framework to follow," she said.

As of September, numerous states have different drinking water regulations in place. New Hampshire, for example, has regulations for four PFAS, including 12 ppt for PFOA and 15 ppt for PFOS. Massachusetts has a proposed limit of 20 ppt for six PFAS combined. Michigan has regulations for seven PFAS, the lowest of which is 6 ppt for PFNA. Several states have also enacted groundwater cleanup standards at the same or similar levels as their drinking water standards.

"That lack of a federal MCL has led to this whole situation you see," said Stephen Zemba, a project director for environmental firm Sanborn Head and Associates. He said "every state [is] having to interpret, if you will, a different set of toxicological data," with differing conclusions about safety and public health.

The experts agreed surface water standards are the next likely target, which will impact landfills. Michigan prohibits wastewater utilities from discharging more than 420 ppt of PFOA or 11 ppt of PFOS. Florida has developed surface water screening levels of 150 ppt of PFOA and 4 ppt of PFOS for freshwater and estuarine finfish and shellfish. While PFOA standards tend to be lower for drinking water, PFOS standards have been lower for surface water as that chemical has been shown to accumulate in fish which are then consumed by people.

Scrutiny of surface water poses a challenge for landfills sending leachate to wastewater treatment facilities. Some of those facilities in states like New Hampshire have begun rejecting leachate due to concerns around future regulations, according to the Northeast Biosolids and Residuals Association, which is closely tracking the issue.

Stormwater discharge permits could also be impacted, speakers said, pointing to a study of the New Hampshire-based Coakley Landfill. Testing suggests compost and sludge used as topsoil for that Superfund site may have spread PFAS through stormwater runoff to drinking water sources. State regulators are scrutinizing stormwater elsewhere. In public comments submitted earlier this year, Massachusetts, Colorado and New Mexico all pushed EPA to take action on permits for those discharges relating to PFAS.

"EPA isn't leading on this, just like they haven't led on the drinking water and groundwater front," said Roy. "The states are really pushing EPA to adopt certain approaches when it comes to PFAS."

Zemba said movement on stormwater discharges is a "big deal" and could come with "significant" costs. Session moderator Ivan Cooper, a national water and wastewater practice leader with the firm Civil and Environmental Consultants, went into broader detail about costs associated with PFAS treatment for leachate, like reverse osmosis and ion exchange. He said most treatments still leave operators dealing with the disposal of residuals, however, and lack destruction capabilities.

"We see some of the costs in the range of five to six cents per gallon for [some] pre-treatment prior to discharge," said Cooper, who added all costs are site-specific and technology-specific.

As water regulations ramp up, speakers said the waste industry should also be preparing for future issues — namely PFAS in landfill gas. "[It's] an issue that's emerging and I think it's going to be a big issue in a year or two when we get some data," said Zemba.

Fugitive emissions from landfills are a given, he added, and research is ongoing to determine the impacts of PFAS in landfill gas. EPA awarded $900,000 to North Carolina State University in 2019 to "characterize and estimate the amount of PFAS present in landfill gas and the amount of PFAS fugitive emissions produced." Zemba said the results will almost certainly find PFAS, potentially at elevated levels, and could spark swift action from regulators.

Preparing for that reality, the panelists said, could save time and money. They advised looking into treatment methodologies and noted some landfills may be collecting data on PFAS and emissions.

"[There's] reason to believe regulators would be conservative about it," said Zemba, referencing future PFAS regulations. But, he added, "industry could be out on the forefront, doing some work beforehand to prepare for the data that are coming out."