Edward Humes doesn’t think he’s solved America’s waste crisis, but he has a few suggestions he thinks might help.

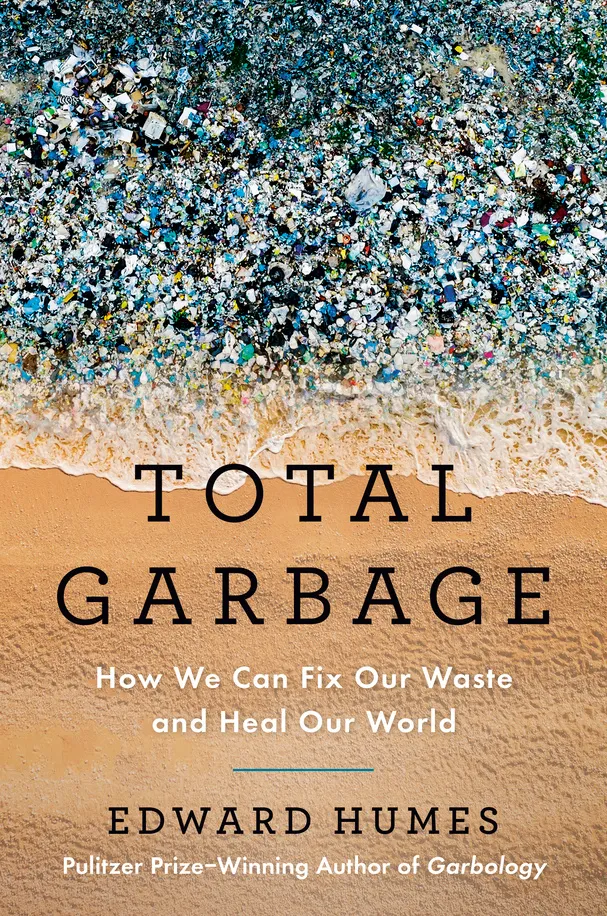

The author and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist takes aim at what he sees as the most wasteful aspects of American culture in his new book, “Total Garbage: How We Can Fix Our Waste and Heal Our World,” out on April 2.

The book showcases numerous waste, recycling and reuse advocates and their quest to reduce waste in everyday life. Along the way, he also introduces experts who connect personal responsibility changes with larger systemic solutions, such as advocating for extended producer responsibility laws and curbing greenwashing through changes to packaging labeling and other efforts. The book reads as a how-to guide for people who worry about reducing their waste footprint but aren’t sure where to start.

Humes already has one waste-related book under his belt: the 2012 book “Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash.” For that book, he explored the scope of the waste problem in the United States by visiting landfills, delving into single-use plastic issues and spending time with advocates trying to prevent plastic in oceans.

But much has changed in the decade since that book was first published: China’s National Sword policy altered the way the U.S. ships recycling overseas, while EPR and other policies meant to raise recycling rates and reduce pollution have taken hold. At the same time, pollution persists and in some cases is getting worse, he said.

For his follow-up book, Humes told Waste Dive he wanted to highlight meaningful steps to reduce waste in everyday life — everything including how Americans source and cook food, how they heat their homes and power their vehicles, what types of packaged products they choose at the grocery store and where they buy their clothes.

“Everywhere you look, there's a lot of wasteful things that have become normal to us and they're not normal,” he said.

“Total Garbage” follows people that Humes said are “thinking outside that normalcy box” to advocate for better solutions. In one part of the book, he describes accompanying Jenna Jambeck, an environmental engineering professor at the University of Georgia and an author of leading studies on plastic pollution, as she gathered food packaging data at a grocery store. The trip showed Humes just how confusing it can be for consumers to choose the most environmentally friendly or recyclable food packaging, something Jambeck herself admitted was tough for her — even with a self-described “PhD in trash.”

Another part of the book highlights Sarah Nichols, then the Sustainable Maine director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, about her work helping to pass the country’s first EPR for packaging law.

“It was so interesting to see how she championed it just one heart and mind at a time — talking to town council meetings, recruiting citizen volunteers to talk up the power of saying, ‘We've shifted to this model of foisting the responsibility for dealing with plastic and packaging waste on to taxpayers and consumers. That’s not right.’”

Though much of his book includes ways the average person can make personal choices to prevent waste, Humes acknowledged that personal responsibility is just one part of the puzzle. “It shouldn’t be about blaming the consumer, but our choices do matter. They should also inform and drive larger policies so responsibility can be shared,” he said.

He also acknowledged that some of the book’s tips — choosing grocery store foods that come in less packaging, for example — aren’t realistic for people who live in communities without grocery store access, meaning the most feasible daily shopping option are convenience stores that sell pre-packaged items. Larger policies are needed to address similar inequities, he said.

“The burden of all that waste falls most heavily on disadvantaged communities… because incentives in our economy allow that,” he said.

Still, Humes feels optimistic that there are more tools available than ever to help individuals fight what he calls “the toxic disposable economy.” He highlights “micro-farms” in Los Angeles that transform lawns into places to grow food and high-end restaurants that have converted from natural gas to induction cooktops to save energy and reduce indoor air pollution. He also mentions a farming community in Minnesota that dramatically reduced its energy consumption by switching to solar and LED power.

Humes himself is an ardent supporter of thrift stores, which he said keep clothes out of landfills and fight the rise of fast fashion, which often is made of materials that contain plastic but have limited or no outlets to be recycled.

“My argument, in most cases, is that not only are some of these options the less wasteful options, but they are the cheaper options. We’re making the economic case, the social and environmental case,” he said.