Environmental justice advocates calling for restrictions on plastic production and pollution squared off against plastic proponents during a heated Senate hearing on Thursday.

A panel with representation from environmental justice communities and plastic business interests alike testified during a meeting of the Subcommittee on Chemical Safety, Waste Management, Environmental Justice, and Regulatory Oversight.

The hearing highlighted conflicting and sometimes contentious views about the roles plastic production and disposal play in health, environmental and economic issues, particularly in environmental justice communities.

Residents who live near plastic production facilities or incinerators testified that halting plastic production and ramping up environmental regulations could help alleviate their serious health issues ranging from asthma to cancer. Yet business groups on the panel said it’s unrealistic to eliminate plastic from daily life and could jeopardize the jobs that plastic production and recycling create.

It was the second in a series of six meetings Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., said are necessary to get lawmakers on the same page about how to handle urgent plastic pollution issues.

"One of the conversations is, how do we distinguish between necessary uses of plastic and those that are not necessary, because maybe we can reduce those harmful effects by reducing how much we produce,” Merkley said Thursday. "And when we produce it, how do we produce it in a way that is less harmful to the communities in which it is located? How do we reduce the emissions and reduce the cancer, the disease rates there?"

Merkley was the co-sponsor of last year’s Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, legislation that included calls for a temporary freeze on permitting for new plastics production facilities so the federal government can investigate their health and environmental impacts.

Sen. Markwayne Mullin, R-Okla., the subcommittee’s ranking member, said it’s important for Americans to have clean air and water, but that goal must be balanced with the country’s ability to manufacture plastics without relying on other countries.

“I don't believe we have a plastic problem, we have a recycling problem,” he said. “We have to learn how to make recycling valuable, where it allows us to be able to use that as a value base. And if we ignore that issue, then you're ignoring the reality, because what is going to replace plastics?”

Mullin criticized Democrats, saying environmental justice “has been transformed away from its original intent of helping poor and marginalized communities with specific needs into a social movement Democrats have taken over to push progressive policies under this guise of social and racial equality.” The hearing turned contentious at times, with audience members calling out phrases like “break free from plastic” and interrupting Mullin’s remarks.

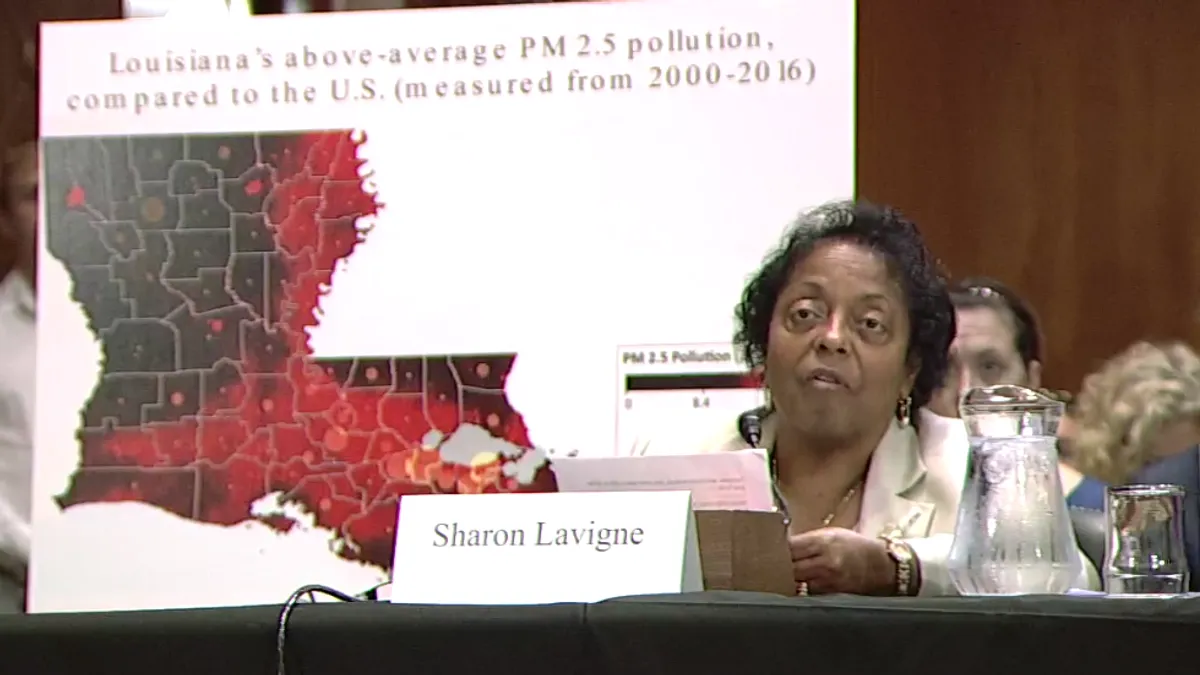

Several speakers urged the subcommittee to understand the grave impacts plastic pollution have had on their lives. Sharon Lavigne, founder of Rise St. James, an environmental justice organization in Louisiana, testified that she lives in an area commonly called “Cancer Alley” because of a convergence of industrial facilities that she said have polluted air and water, making her and her neighbors seriously ill. Her group is currently fighting to prevent Formosa Plastics from building a plastics plant in St. James parish. “It seems I am now heading for funerals just about every week for another neighbor or friend,” she said.

She called on the U.S. EPA and other agencies to “use the tools they already have” to enforce environmental violations and better monitor the region. She asked Congress to pass laws that “stop building petrochemical and fossil fuel projects here in St. James and everywhere… They get tax breaks, and we get sickness and death. And for what? All in the name of profit.”

Other speakers testified in favor of stricter state environmental justice permitting processes. Chris Tandazo, director of government affairs for the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance, said the state’s recent adoption of a landmark EJ permitting law “is a beacon of hope for communities like mine.” Tandazo grew up in an area of Irvington, New Jersey, where living in close proximity to pollution from industrial facilities “was seen as normal.”

The EJ law requires the state to evaluate the environmental and public health impact on “overburdened communities” during certain permit expansion or renewal applications for some facilities.

Tandazo also called for plastic reduction legislation that would help decrease the amount of plastics that could eventually be disposed of in one of the three incinerators in New Jersey, “all of which are located in low-income communities of color.”

Other speakers were skeptical of proposals to further regulate plastics manufacturing or disposal. “I think that all manufacturers are subjected to extraneous regulations,” said Donna Jackson, director of membership development for the National Center for Public Policy and Research, which she described as a Black conservative think tank. “American manufacturers are subject to the most rigorous environmental standards in the world, including plastic plants.”

She sees industrial jobs as an “overwhelmingly positive thing for struggling communities,” because such jobs are often available for people without advanced degrees and can help bring families out of poverty.

Kevin Sunday, director of government affairs at the Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry, added that states can find ways to protect the environment while also supporting jobs. Pennsylvania’s chemical industry relies on petroleum manufacturing for economic stability and to keep about 55,000 people employed, he said. Environmental justice communities “want jobs, so we must embrace and pursue tax and regulatory policy that doesn't drive investment away from these communities,” he said.

The state’s EJ approach is to “ensure public participation from impacted communities,” a process he said is working well. Sunday didn’t mention projects by name, but said a refinery project in Southeastern Pennsylvania has been recognized for its engagement with environmental justice communities. And he said a plastics recycling project in Erie “is empowering the community to increase their own waste minimization efforts.”

Some lawmakers during the hearing expressed concerns about future consequences of plastic regulations. "One thing I do worry about is that if we crack down on plastics here, production of that, it's just going to drive it overseas to China, places that don't have strong environmental standards like we do," said Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska.

But Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., said he is about to reintroduce his REDUCE Act bill meant to put a 20-cent-per-pound fee on the sale of new plastic used in single-use products. He pointed out that numerous major companies are already working on goals to reduce plastic packaging and increase recycled content. “If a company like Unilever is already doing that, that shouldn’t be asking too much of American companies,” he said.