Last spring, as coronavirus restrictions reversed single-use bag bans, plastic film was once again in the limelight. The thin, flexible sheets of plastic are best known for their use in grocery store bags, but get used prolifically in everything from the packaging on Twinkies to bubble wrap.

“With COVID, a lot of folks actually went back to using the single-use bags from the reusable shopping bags, from a health and hygiene and sterility safety perspective,” said Alison Keane, president and CEO of the Flexible Packaging Association. Film’s ability to hold up well in shipping and keep perishables fresh, all the while scoring well on life cycle assessments, is the reason why interest in it is only growing.

Yet those same fears — about health, hygiene, and sterility — had another unforeseen effect. As reasons to use plastic film climbed, the already limited avenues through which to recycle it appeared to dissolve.

“A lot of stores got rid of their front-of-house recycling bins,” said Keane. “That's been an unfortunate aspect.”

Because they can damage recycling equipment and contaminate bales, plastic films and wraps have long been an unwelcome item in most curbside streams. Instead, the plastics industry has advocated for a system of drop-off bins placed at the front of supermarkets and big box retailers as an alternative recovery method. Consumers, when they participate, stockpile this material in their homes and bring it in themselves.

The list of complaints from critics against the take back programs includes everything from inaccessibility and low participation rates to high levels of contamination that some say renders the contents of the bins unacceptable.

“They can't use COVID as an excuse, at all,” said Jan Dell, an independent engineer and founder of the nonprofit The Last Beach Cleanup.

Dell has been monitoring the efficacy of the take back bins. In one instance, she traveled to retailers in California listed on the website of the Wrap Recycling Action Program (WRAP), an initiative launched in 2013 by the American Chemistry Council (ACC) to raise awareness about the recyclability of plastic films.

“There were supposed to be 52 in an area for 1.6 million people,” she said. “We found only 18.” It was this scarcity that, as of January 2020, prompted California to end its legal requirement for stores to have take back bins. WRAP’s website says that due to “ever-changing conditions, stores may discontinue their programs… without notice.”

Dell and others worry that issues with the program far transcend the COVID-19 pandemic, and mask a much more dire situation with plastic film recycling in general. Industry critics and stakeholders alike recognize that current end markets are incapable of processing the immense volume of plastic film generated each year: 9 billion pounds in 2018, according to the ACC’s latest report.

While some advocate for maintaining the system and improving end markets through legislation and sustainability goal post-setting, others say it is time to abandon ship. Some in that camp favor chemical recycling alternatives, which they say would simplify the waste sorting process. Others, like Dell, favor simply disposing of the film until it can be replaced with other packaging materials.

In the meantime, ambiguity around the recyclability of plastic film, bags and wraps can have the unfortunate consequence of allowing the material to end up in curbside bins: the very stream the store drop-off programs were designed to help bypass in the first place.

The tenability of take back

The last decade has seen the recycling industry simplify its sorting processes and shift to single-stream collection in many areas. Plastic film has largely not been part of this trend, as recyclers do not want it in their conventional curbside streams. To their dismay, it often ends up there anyway and workers have to put themselves at risk trying to clean it out of MRF equipment.

However, producers of film, including companies represented by the American Chemistry Council, also don't want it going to landfills or incinerators. The mono-material polyethylene from which a majority of film, wraps and bags are made is in theory highly recyclable. The ACC’s Plastics Division announced in 2018 a goal for 100% of plastics to be "recyclable or recoverable" by 2030.

According to Craig Cookson, senior director of recycling and recovery at the ACC, several of the plan's key elements include “how to turbocharge the collection and the sortation of more challenging types of plastics like film.” And as pressures rise for brands and retailers to increase the recyclability of their packaging — Walmart, for instance, has pledged that 100% of its packaging will be recyclable by 2025 — making film more recyclable helps ensure its continued ubiquity across the consumer landscape.

The solution over the last decade has been to treat plastic film as a category of its own, with specific rules for collection, sorting and recycling. For consumers, those rules have revolved primarily around the store drop-off bins (though the ACC has more recently invested in curbside recycling pilots for certain types of film, too).

“There is a whole array of polyethylene film that has an infrastructure for recycling through retail take back,” said Shari Jackson, director of film recycling at the ACC, who oversees WRAP. “We’re trying to optimize that system, so that more of that existing material is collected, is recycled, is supporting existing end markets and emerging markets.”

The ACC has also forged coalitions and partnerships, with the goal of bolstering public education on film recycling. Examples include a 2016 memorandum of understanding with the U.S. EPA, or funding infrastructure like The Recycling Partnership’s “Accelerate Recycling” proposal, which promotes packaging fees to help pay for more recycling infrastructure and education.

Since 2005, when the ACC started monitoring it, the collection of film has increased 54%. This is not just from take back bins, but across the board and includes shrink wrap from back-of-house shipping pallets, film used in agriculture and even the stuff that gets sorted out at MRFs from what is accidentally placed in curbside bins.

But given the widespread prevalence of plastic film across nearly every segment of the consumer experience, what's collected is still just a small sliver. The EPA estimates that in 2018, Americans generated nearly 9 billion pounds of PE films, bags and wraps annually. Some argue that figure could be much higher, pointing at data from California, where film made up 2.6 billion pounds of the waste stream in just one state. Of the EPA’s 2018 figure, only 11% of film was recovered. Within that, the contents of retail bags and film made up 242 million pounds.

“It’s not just the take back bins,” said Dell, critiquing their efficacy. “It’s that no one actually buys that material. It is so contaminated.”

Not only are bins often mistaken for garbage cans, attracting non-film items that contaminate materials with leftover food or liquids; sometimes, even perfectly recyclable film is made unacceptable at the point of sale thanks to labeling practices.

“We prefer they not be on there,” said Jackson, referring to stickers — like barcodes or shipping labels — which many retailers and distributors affix to products made with plastic film. “Putting the material itself in there sans the stickers, all of that helps to improve the quality.”

Dell said the specifications for many film end markets are much higher grade than what is ending up in bins. She pointed specifically to Trex, a company that produces alternative decking and uses film as feedstock for its products. Alternative lumber accounts for 46% of the PE film end market, Trex is the leading producer in that market. Yet its specifications for quality include everything from stipulations on cleanliness (no moisture, food or loose paper) to color requirements (“less than 5% blue colored bags”), which Dell maintains is a nearly impossible standard for take back bins.

Jackson did not identify the average rate of contamination in these bins, but said education campaigns do much to improve the quality and referenced a 2018 initiative where ACC partnered with the state of Connecticut with positive results. She also said Trex does take post-consumer material alongside back-of-house post-commercial film, and noted ACC is working on developing new end applications for recycled film that would lower specification requirements, like asphalt.

“That has been done in other countries and has been piloted here. But it is an alternative large scale end-use for that material," said Jackson.

Eadaoin Quinn is director of business development and procurement at Canada-based EFS-Plastics which both purchases and processes post-consumer film into new film applications, which she says is “a higher end product that allows us to handle some of the more contaminated material.”

Quinn stands by the bin collection concept, particularly when picked up in conjunction with back-of-house film as reverse logistics are already in motion.

“From my perspective, the store drop-off program is the preferred way to recycle film,” she said, arguing that while take back bins may look contaminated, they’re a better option than letting film enter traditional recycling streams.

At the same time, she also said collecting film from store take back programs doesn’t really make economic sense as a standalone concept.

“If it was just the store take back, it would be hard to reach the volumes necessary to make a truckload and it would be too contaminated on its own.”

Between 70% and 80% of the bales picked up by EFS-Plastics consist of “back-of-the-house shrink wrap,” the clear film used to cover shipping pallets containing goods for supermarkets and big box stores. Quinn described that material as more homogenous, and more dependable.

“In general, that's what people are buying, they know that it's going to be mostly the shrink, and it has some other material," she said.

But Quinn said the bins are also the least of her worries. What keeps her up at night are the higher-level economics of it all, particularly as oil prices continue to decline. That lowers the cost of virgin plastics and makes plastic recycling markets across the spectrum less competitive. “The demand is what we need to be talking about first,” she said.

“I think in general, we've approached the challenge of film recycling from the opposite direction," said Quinn. "People have been very concerned about where they put their plastic bag after they’re done with it and where do they go, without really thinking about are they actually going to be using this in North America to turn it into something new? Which to me is the more important question.”

End market limitations

In the last two years, international markets – which once made up over half of all end markets for recycled film – have plummeted. This is seen as a direct consequence of China’s 2018 import restrictions on various commodities, including plastics. According to an ACC report, export purchases of film were already down 46% between 2016 and 2017, resulting in a 24% overall decrease in post-consumer film recovered.

But the situation is not without its silver linings, said Quinn. For the last six years, domestic markets have been on a steady incline now that they face less competition with smaller factories in developing countries, “where they don’t have to worry about environmental rights and labor quality," she said. Quinn expects this trend to continue.

“Operating in Canada and Pennsylvania, it’s really incomparable the type of operation we’re doing versus what might happen to it if it is exported,” she said.

Moving forward, Quinn hopes legislation like California’s SB 270, which mandates a minimum 40% post-consumer recycled (PCR) content in reusable plastic retail bags, will help ensure end markets. Similarly, legislation is being considered in New Jersey (A4676) that would mandate an end market for recycled content in garbage bags. This is an area Quinn identifies as especially low-hanging fruit, since they “aren’t something we’re going to do away with anytime soon.” Under the bill, trash bags sold in the state would have to consist of at least 10% post-consumer recycled content which is not often the case.

“We just should not be making garbage bags out of 100% virgin material,” she said. “It doesn't make any sense when there can be recycled content and it's proven that we can do it… Sure, we could get to 100%, but why the heck aren't we even doing 10%?”

Though domestic processing capability has been growing in the U.S., Dell still argues it is nowhere near sufficient. In California alone, a survey of nearby facilities found recycling capability for less than 4% of the film generated by the state.

In this context, programs like Novolex’s oft-touted Bag-2-Bag program, which processes 22 million pounds of post-consumer film from store take back bins every year at its recycling center in North Vernon, Indiana, is a fraction of the remaining 8 billion pounds (a conservative estimate, some say) that requires processing annually.

In a statement, Novolex said demand for recycled content products “remained high” and that “with several states mandating post-consumer content levels in bags, we expect this demand to continue in future years."

A different approach

In many ways, the debates around film recycling mimic those being held in the broader plastics category. For all the work and investment it requires to collect material, sort through it and develop suitable end markets to which it can be sold, some worry that the current process of recycling is not designed for longevity.

“Every pass [materials] go through, they’re being degraded and degraded and degraded,” said Bruce Welt, a professor of packaging science and engineering at the University of Florida. “We're tolerating the lousy properties, trying to find what is the limit of our tolerance… in what we're making from this stuff.”

In Quinn's view, “while that is certainly a problem that we should be thinking about for the future, it is not the problem today.” Degradation in film is not a deal breaker, she said, so long as there are end markets. “It will be an exciting day, when there's just too much recycled material that made it into a new product, and then it's ending up in the recycling bin enough that it’s actually at a point where it's affecting the quality. We're extremely far away from that.”

But Welt argues mechanical recycling’s shortcomings require immediate attention, especially considering the painstaking lengths it requires to sort out contaminants, which is “mission critical” in today’s market.

“If you don't purify each stream, then the whole thing falls apart. But quite frankly, no matter how much we invest in it, we're still not very good at it and we're never going to be,” he said, alluding to the growing use of newer packaging types that aren’t widely accepted in curbside programs or retail take back bins.

Welt says a better approach might be to discard the sorting process not just for films, but for all waste streams.

He and his team at the University of Florida advocate instead for a process called plasma-assisted gasification. This is a more advanced form of gasification – a well-known process in the chemical industry – that is traditionally used to convert any carbon-based material (most often coal) to a syngas that provides about one-sixth the energy of natural gas. The initiative Welt’s team is working on hopes to take that a step further by converting the syngas output into methanol, a basic and easily transportable primary feedstock for making “just about everything.”

The ACC has also expressed interest in chemical recycling; not as a replacement for mechanical recycling, but as an alternative for more difficult materials, like mixed plastic containers and film.

“It’s really able to take a wider variety of film,” said Cookson, “and deal with the contamination in a lot of ways: your pouches, your snack wrappers, your frozen pea bags, things like that.”

But according to Marco Castaldi, a City University of New York professor and director for the Earth Engineering Center, the debate over gasification is a long one in the making. He views the question of plasma-assisted gasification as even more complicated.

For one, plasma, in comparison to other forms of chemical recycling, requires a higher energy expenditure to create syngas. But even then, Castaldi said, “making synthesis gas, that's the easy part. The hard part is taking that synthesis gas and making the methanol.”

While he said the equations may seem straightforward on paper, in reality he noted the system is unpredictable and efficiencies are sometimes as low as 50%.

Castaldi said he prefers methods which may be less energy intensive – like combustion, regular gasification or pyrolysis – over plasma-assisted gasification, but that “I would take any one of those over doing nothing."

"I would take any one of those over trying to just force more recycling, because [a lot of these materials] can't be mechanically recycled,” he said. “Until we get to the market to absorb recycled stuff, let’s keep it out of the landfill."

What's next

In the meantime, as far as film is concerned, critics worry the existence of separate channels only further obfuscates an already confusing system.

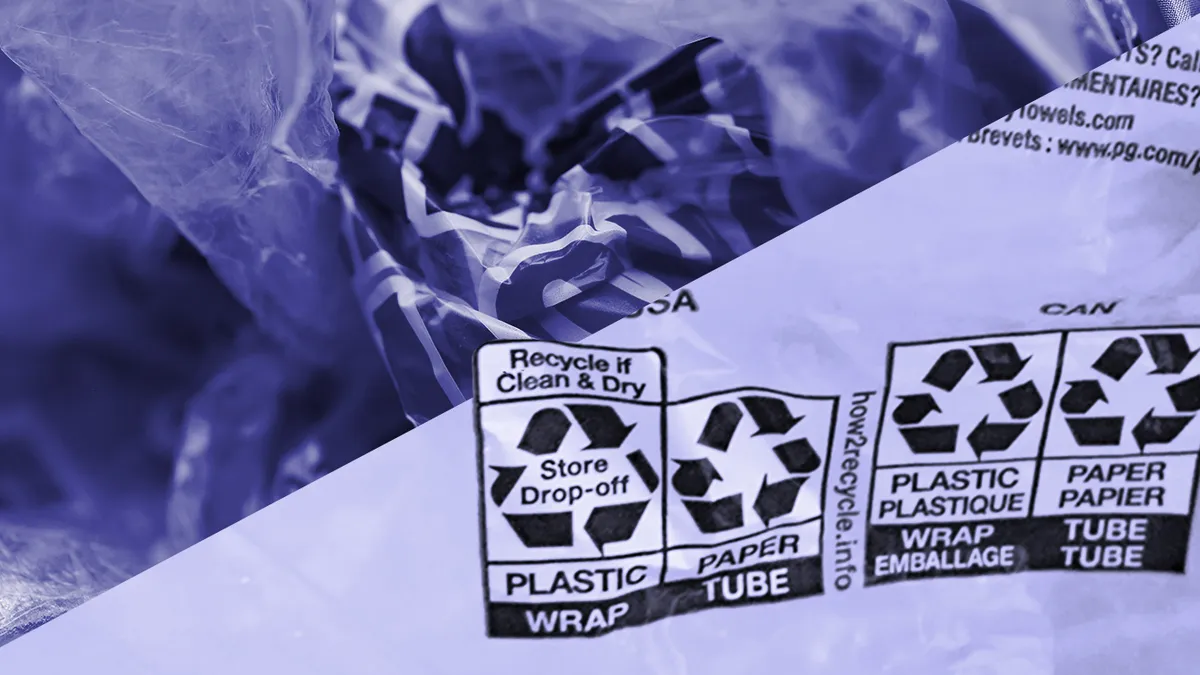

Likely hoping to meet sustainability targets involving recyclability, many companies apply the universal recycling logo on their film products. The symbol is accompanied by the words “Store drop-off,” as part of How2Recycle, a labeling system spearheaded by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, which has come under criticism for making certain products seem recyclable even if limited options are available to most consumers.

Due to a high volume of complaints, the WRAP website states its “directory is NOT affiliated with the How2Recycle label, Amazon or other brands,” and tells consumers to “direct specific questions about the How2Recycle label to Info@GreenBlue.org or contact specific brands and companies about their products and packaging.” The organizers of the How2Recycle program did not respond to a request for comment.

Consumer confusion over film recycling is evident in the high rates of contamination that persist in curbside recycling bins across the country.

In California, film products account for 12% of contamination in the plastics category by weight. In the summer of 2018, Cambridge, Massachusetts, performed an audit of 1,165 carts, of which 52% contained contamination from plastic bags, films and wraps. According to Michael Orr, the city's recycling director, that figure has decreased dramatically following the state’s “Recycle Right” education campaign, but it’s unclear where the film is ending up now instead.

Responding to these concerns, the California Commission on Recycling Markets and Curbside Recycling recently recommended recycling labels be removed from plastic film products and replaced with language instructing consumers to dispose of them as trash.

“Our recommendation is that we just need to flat out call this stuff what it is, which is trash,” said Dell, a commission member. “Because people are putting them in the recycle bins instead and they're not recyclable.”

Nearly a year into the pandemic, film take back programs are beginning to reappear at some retail locations and the conversation about plastic film has taken on new dimensions after initial concerns over virus transmission – which have turned out to be unfounded.

“Before, there was a lot of cultural momentum against the single-use plastic bags,” said Welt. He believes the pandemic has forced many to reckon with the advantages of lightweight single-use plastics, particularly as it pertains to personal protective equipment as well as sustainability goals that encourage materials to be increasingly lighter to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Film, the most lightweight category in plastics recycling, is caught up in this mix of these competing public health and sustainability agendas.

“We talk about ‘reduce, reuse, recycle,’” said Welt. “Reduce is the only one that has been shown to have a benefit, and the films are a product of reduction… But where to go from there?”

Even if film manufacturers and recyclers were to perfect their collection methods in the short term, Keane of the Flexible Packaging Association said it won’t fix the looming challenge of end markets that currently can’t seem to keep up.

“You can have all the infrastructure in the world,” she said. “But if you're going to make a big flash sale and nobody's gonna buy it, then it's still going to go to landfill.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated participants involved in the survey of available take back bins in California, as well as the volume of retail bags collected for recycling.