As the waste industry awaits new federal guidance, states are developing regulations and laws on how to manage PFAS in everything from packaging to clothing to biosolids. The question for waste companies is how these decisions could affect daily facility operations down the line.

The U.S. EPA is not expected to develop standards for certain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances until next year, but the waste industry has asked Congress to grant MSW landfills a narrow exemption from liability if certain PFAS eventually are designated as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA.

In May, the National Waste & Recycling Association and the Solid Waste Association of North America submitted a joint letter to the Senate environment and public works committee, arguing that CERCLA regulation could have unintended consequences, such as forcing landfills to restrict PFAS-containing waste; could raise the costs for managing the material; or could force landfills to pay litigation costs in PFAS-related lawsuits. MSW landfills are passive recipients of PFAS-containing items, and they do not otherwise manufacture or use PFAS, thus they should not have to be liable for PFAS contamination issues as they consider themselves “part of the long-term solution to managing these compounds,” the letter stated.

In the meantime, some of the recent, relevant PFAS management updates have come from states that are motivated to reduce residents’ exposure to the substances and take a more proactive approach to the chemicals, said Craig Butt, a PFAS scientist at SCIEX. “The states are not waiting for the federal government to make a decision. They're being more proactive, so we’re seeing more state-level decisions come online,” he said.

Recent PFAS actions that could impact the waste and recycling industry in the coming months and years include the following.

Addressing PFAS in packaging

Several state and local governments, along with environmental groups, have turned their focus to legislation that would phase PFAS out of consumer goods and food packaging. These bans or restrictions are meant to reduce everyday human exposure to the chemicals, but they could also have a long-term impact on landfills and the costs associated with managing PFAS at their facilities, said Lauren Tamboer, a communications consultant for the Washington State Department of Ecology.

“This is meant to be a benefit to waste streams because it reduces sources of contamination entering those waste streams,” she said. “It's just a more preventative approach. It's cheaper than cleaning it up in the environment once the chemicals have already been released.” The waste industry also favors this upstream focus.

Though it’s not clear exactly how big an impact these laws could have on the amount of PFAS entering disposal over time, PFAS-related rules could directly affect operations costs, said speakers at WasteExpo in May. At the conference, the Environmental Research & Education Foundation estimated that the incremental cost to treat PFAS within leachate could impact tip fees from 3% to 14%, based on a national $54-per-ton average, Waste360 reported.

Washington is one state working to phase out PFAS in packaging as part of a multiyear plan to address PFAS-containing products like apparel, firefighting gear and cosmetics under the state’s Safer Products Law. Gov. Jay Inslee recently signed HB 1694, which speeds up the timeline for the state's Department of Ecology to act on restricting numerous products containing PFAS.

Ecology last week also published the second part of its anticipated report identifying packaging alternatives that do not contain PFAS. The research is part of an ongoing process of banning specific types of food packaging containing PFAS once “safer alternatives” are identified. The process is also meant to avoid substituting packaging with what Tamboer calls a “regrettable alternative” that might contain a different type of chemical that could cause health concerns or disposal issues down the line.

Washington sees itself as having an aggressive timeline for its PFAS management plan, but Tamboer said other states will soon take up their own PFAS management laws that could be as strict or stricter. “These are emerging regulations. There will be a lot of restrictions moving forward, and I think guidance is going to get better and better,” she said.

In Colorado, the sale of many products containing intentionally added PFAS — including food packaging, carpet and products meant for children — will be prohibited starting in 2024 if Gov. Jared Polis signs HB22-1345. Cosmetics, indoor textile furnishings and indoor upholstered furniture with PFAS would be prohibited in 2025, and outdoor textile furnishings and outdoor upholstered furnishings with PFAS would be prohibited in 2027, according to the bill. U.S. PIRG, a supporter of the bill, sees Colorado’s actions as one step in a broader effort. Emily Rogers, a PIRG Zero Out Toxics advocate, anticipates other states will adopt such bills in the future to “turn off the tap on PFAS contamination across the country."

As the general public learns more about PFAS and its potential health impacts, more companies are announcing voluntary phaseouts of PFAS in packaging. Starbucks announced it would eliminate PFAS in its U.S. packaging by the end of the year and eliminate it from its global packaging in 2023.

Both McDonald’s and Burger King had earlier pledged to remove PFAS from their packaging, but after a recent report from Consumer Reports found significant levels of PFAS in the restaurants’ packaging, both companies are facing lawsuits for alleged false advertising and deceptive business practices.

Packaging producers will need to keep a close eye on such lawsuits, Butt said, as the outcomes could shape state policies on what types of packaging can be sold into certain states or regulations on how PFAS from certain packaging should be managed down the line. Consumers also need to read company pledges carefully to determine exactly what companies are promising when they make PFAS-related claims, he added.

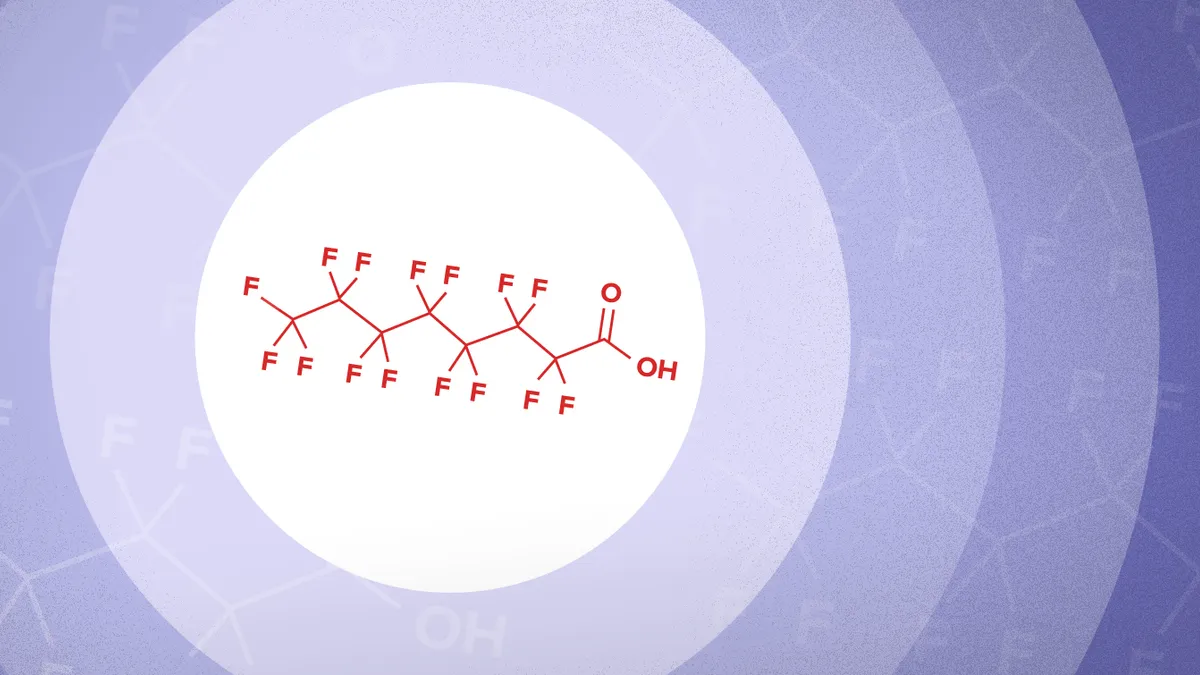

“Are they saying they will eliminate all PFAS, or just PFOA? The wording matters."

Other state PFAS bills to watch

States are also working through legislation that would more strictly regulate PFAS in drinking water and soil or restrict disposal of certain types of PFAS:

- Illinois: Lawmakers in Illinois have passed HB 4818, a bill that would ban incineration of certain materials listed under the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory that contain PFAS, such as firefighting foam. The bill includes exemptions for the combustion of gases at landfills, medical waste incinerators and byproducts generated by municipal wastewater treatment facilities, according to state Sen. Christopher Belt, a sponsor of the bill, in a statement. The bill has been sent to Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker for his signature. Pritzker last year vetoed a similar bill, but this year’s version of the bill aims to clarify that incineration does not include the use of thermal oxidation for the purposes of pollution control, Belt said.

- Maine: In April, Gov. Janet Mills signed a law prohibiting the land application of biosolids from a wastewater treatment plant and the sale of compost containing the biosolids because of concerns they contain PFAS. The new law could send more municipal biosolids, which are sometimes used as fertilizer, to landfills in Maine or surrounding states, causing logistical and capacity issues and further complicating landfills’ leachate treatment processes, panelists at WasteExpo said. Other states could consider their own similar bans, the speakers said.

- Florida: HB 1475 is awaiting Gov. Ron DeSantis’ signature. The bill requires the state's Department of Environmental Protection to adopt cleanup rules and targets for PFAS in drinking water, groundwater and soil in certain cases, focusing first on PFOA and PFOS. The rule goes into effect if the U.S. EPA does not finalize its standards for PFAS in drinking water, groundwater and soil by Jan. 1, 2025.

Recent EPA moves on PFAS

Though experts say the states are most likely to move quickly on new and updated PFAS laws and regulations, the U.S. EPA is also making decisions that could soon affect the industry.

Emily Lamond, an environmental attorney with law firm Cole Schotz, expects the EPA to stay on track with the targets it announced in its PFAS road map back in October, including its intent to publish more detailed data on PFAS disposal and destruction guidance by the end of this year and to update its guidance by 2023.

The EPA is still expected to designate certain PFAS as hazardous substances and set drinking water standards for certain PFAS sometime next year — two decisions many waste facility operators consider key for determining how they will need to measure, manage or dispose of PFAS-containing items in the future.

The EPA in May also announced it would add five PFAS to its regional screening and removal management levels, though Lamond said the designation likely won’t affect landfill operations unless they are already named in a Superfund case.

Last week, the EPA also awarded Virginia Tech $800,000 to develop a low-cost technique to measure hazardous air pollutants and contaminants such as PFAS. The study’s focus on finding cost-effective strategies aims to be accessible to underserved communities experiencing poor air quality, as part of the Biden administration’s efforts to address environmental justice concerns, the EPA said in a news release.