As federal and state regulators look to strengthen regulations for PFAS, deep well injection is attracting increased interest as a disposal method.

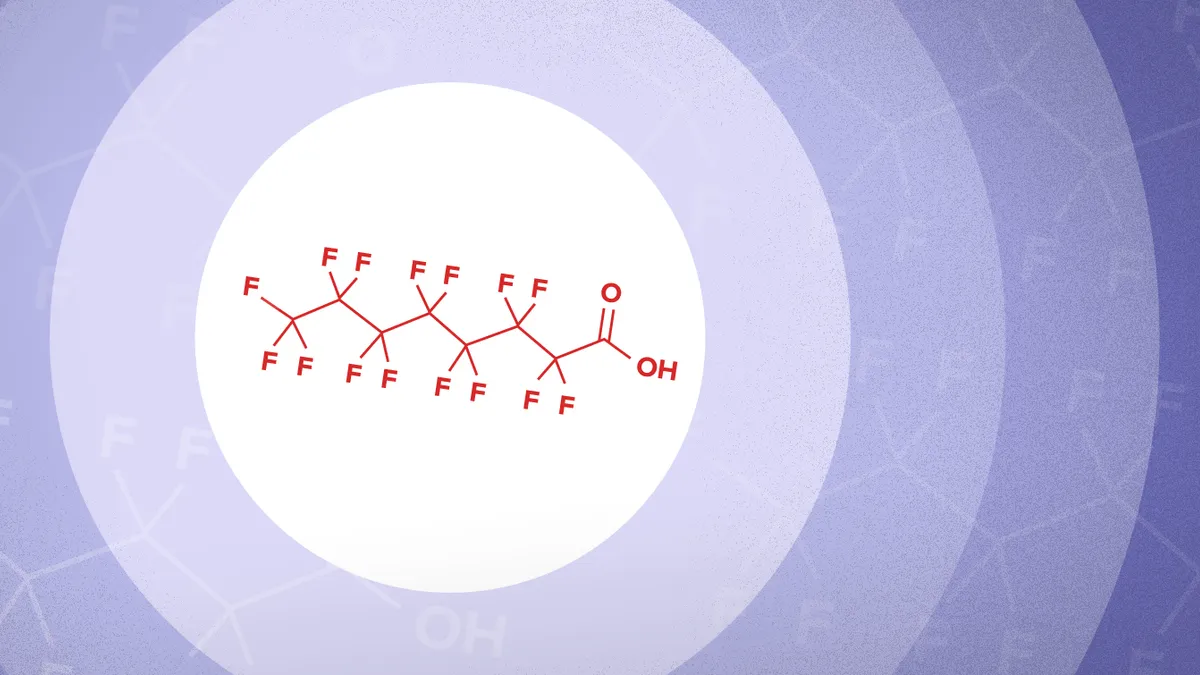

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — a class of human-made, water-repelling compounds found in products as diverse as food wrappers, raincoats and firefighting foam — can persist in the human body for many years. They have been linked to multiple health problems, including cancer, liver and kidney damage, and reproductive issues.

Over the past two years, U.S. EPA has issued multiple proposals aimed at accelerating cleanup of PFAS contamination and limiting their use, including a move to designate certain PFAS as hazardous waste. The efforts are part of an overall goal to “proactively prevent PFAS from entering air, land, and water at levels that can adversely impact human health and the environment,” according to the agency. Several states are also working to speed PFAS cleanups.

The spate of new regulation has created a greater need for PFAS disposal options. Destroying PFAS is difficult, and methods to remove the chemicals often produce waste that needs to be managed. EPA guidance issued in 2020, due to be updated this year, identified three preferred PFAS disposal methods based on the latest science: landfills, incineration and deep well injection.

Landfilling or incineration is used for contaminated textiles, soil, fly ash and other solids. Deep well injection is the preferred disposal method for liquids such as spent cleaning solvents, landfill leachate and firefighting foam. According to the EPA guidance, which analyzed PFAS materials that are not consumer products, deep well injection has “lower uncertainty” around potential migration into the surrounding environment than the other two options.

While the EPA moves to regulate PFAS in various ways, states are also placing new restrictions on how PFAS waste can be managed. New York and Illinois recently banned the incineration of PFAS-containing firefighting foam. Maryland prohibits both landfilling and incineration of that material, leaving underground disposal as the only option other than storage until other disposal methods are developed.

Injection options

Some established deep well disposal facilities, such as Texas Molecular in Deer Park, Texas, are already fielding more inquiries from entities looking for a disposal method for PFAS that will comply with the requirements that come with a hazardous waste designation.

“There are a growing number of clients who are considering our facility,” said former Texas Molecular President Frank Marine in an email. EPA’s interim guidance for the disposal of PFAS “has caused some clients to evaluate sequestration in our hazardous waste injection wells based on their need to find a low-risk solution for PFAS,” said Marine, who now handles business development for the company after its recent sale to VLS Environmental Solutions.

Over the past five years, the Deer Park facility has accepted close to 100 million gallons of aqueous PFAS waste, and has the annual capacity to accept another 100 million gallons of hazardous waste, including PFAS, at its three injection wells. The company’s Corpus Christi facility holds additional capacity. “We expect continued growth as regulations become enacted,” Marine said.

US Ecology (a Republic Services subsidiary) also operates a deep well disposal facility in Winnie, Texas. The company declined to answer questions, but its website notes that the facility is “strategically positioned to accept waste from all over the U.S., with large volume capacity and capable of accepting high-concentration PFAS liquid waste.”

PFAS does not require any special treatment compared with other hazardous wastes, Marine said. The chemicals are handled under the existing federal protocols for hazardous substance disposal in deep wells, which include stipulations to ensure the chemicals cannot migrate from the geological formation used for disposal.

Under EPA requirements for deep well injection, hazardous waste of any kind must be disposed of in a location that is geologically stable, with protective, impervious rock above and below the formation in which the waste will sit. Other considerations include seismic risk and pressure within the formation. Disposal facilities also have to show that the waste will remain secure for at least 10,000 years.

When asked about deep well disposal for PFAS, the EPA said that the agency’s underground injection control rules “prevent the movement of contaminants out of injection formations and into underground sources of drinking water.” The formation where the liquid waste is placed lies far below underground drinking water sources and wells are lined in cement to prevent leakage on the way down. In addition to requirements for siting and well construction, federal regulators also require regular testing and monitoring of the wells.

Nationwide, according to the agency, there are about 800 “Class I” wells, which are used by chemical manufacturers, municipal wastewater treatment facilities, oil refineries and other entities to inject both hazardous and non-hazardous wastes deep underground. But only about 17% of Class I wells are used for hazardous waste disposal. Most are in the Gulf Coast and the Great Lakes regions, which the agency said are geologically ideal for these wells.

Assessing risk

Currently, the most widely used disposal methods are landfilling and incineration, but both have certain drawbacks.

As water percolates through a landfill, it can leach pollutants from the waste, including PFAS. The leachate is typically collected and either sent to a publicly-owned wastewater treatment facility or treated on site, but the sludge or other material produced by PFAS treatment requires disposal. At older landfills that do not have leachate capture systems, landfill runoff can potentially end up in groundwater or surface waters such as rivers and lakes.

Incineration uses high temperatures of 1,000 degrees or more to break the tenacious carbon-fluorine bond that makes PFAS so durable, but “it is not well understood how effective high-temperature combustion is in completely destroying PFAS,” according to EPA’s interim guidance on PFAS disposal.

A 2020 analysis that evaluated a specially-designed thermal oxidizer to destroy PFAS at a Chemours facility near Fayetteville, North Carolina, found that 99.99% of five PFAS chemicals were destroyed. EPA notes that the chemicals leftover after combustion can potentially combine to create other types of PFAS, a process that is not well studied.

Deep well injection comes with the least amount of unknowns, according to the EPA guidance, but the technology is not without its limitations. Location restrictions, the limited number of wells that currently receive PFAS, limits on concentrations of suspended solids, and transportation costs “may significantly limit the practicability of this disposal option,” the EPA noted.

Studies on the effectiveness of PFAS disposal in deep wells are few. Deep well facility operators note that wells have been used to sequester hazardous waste since the 1950s. But public concerns over contamination of underground drinking water supplies persist, and some environmental groups oppose deep well containment.

In a 2021 letter to the EPA submitted during the public comment period on the PFAS disposal guidance, the Environmental Working Group and other advocacy organizations said that deep wells “were not developed and verified for such compounds and can be expected to pose a continuing public health threat and clean up burden.”

One thing that airports, wastewater treatment facilities, chemical companies and other entities needing to find a home for liquid PFAS waste will not have to worry about is having to compete for well space with carbon dioxide disposers.

While the increased demand for hazardous waste disposal coincides with increased demand for underground carbon sequestration to tuck away carbon dioxide captured at industrial facilities, the two types of pollution are managed under different requirements and are not likely to conflict. “I do not expect competition from carbon sequestration wells with sequestration of PFAS in hazardous waste injection wells,” said Marine.