Neil Seldman is co-founder of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and the director of its Waste to Wealth Initiative.

The idea that corporations that produce waste should pay to clean it up is undeniable and uncontroversial. The idea that they should be in charge of the funding and structure is nonsense.

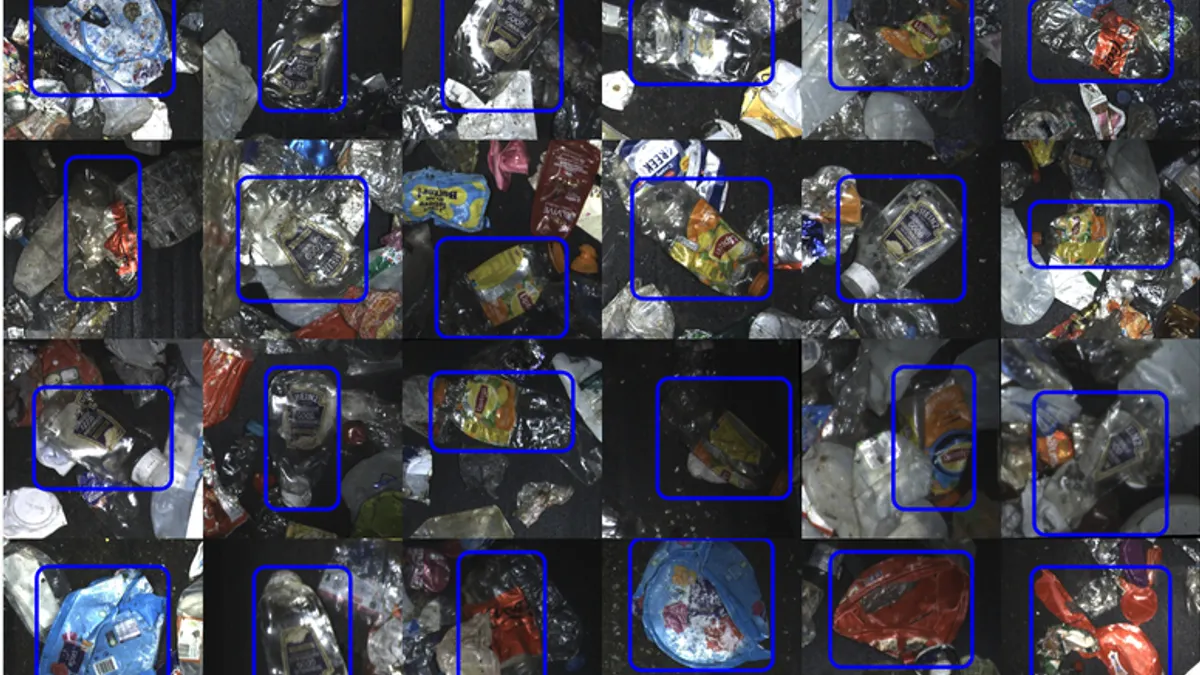

Corporate dominance over municipal recycling proved to be a recipe for disaster. The single-stream recycling system imposed on cities and counties was sloppy and wasteful, even as it was profitable for the vertically integrated waste corporations. The system collapsed in 2018 when the Chinese economy no longer needed materials with up to 40% contamination. This was a blow to the grassroots recycling movement, which had painstakingly built the municipal recycling infrastructure — from drop-off to curbside.

Corporate control over the recycling system through an extended producer responsibility framework is a direct threat to a recycling ecosystem and movement that has overcome huge obstacles to move from the margins to the center of the solid waste debate. This history is critical to appreciating the context of the current EPR debates throughout the U.S.

How we got here

In the 1970s, recyclers were largely dismissed as irrelevant by the industry. In the 1980s, they began to build systems that could recycle 25% to 40% of the waste, overcoming a wave of proposed incinerators — a technology cities saw as a way to avoid asking households to inconvenience themselves with recycling. In the late 1990s, as the recycling infrastructure matured and became a clear alternative to landfills and incinerators for city managers, Wall Street warned large waste management firms that recycling was eating into their profits and if their stock prices fell they would no longer be able to shore up their monopolies with further acquisitions.

In the late 1990s, Big Waste successfully persuaded cities to install a single-stream recycling system where households could dump all recyclables into a single container and end dual-stream collection, which segregates paper to get cleaner materials.

Within a decade, most cities adopted single-stream systems because they were convenient, provided collection at a lower cost and promised higher recycling capture rates. But single-stream recycling froze net recycling levels for almost two decades and led to increased contamination, which is why China eventually banned imports of recyclables from the U.S.

The collapse in 2018 saw more than 100 local governments, based on Waste Dive research, cancel curbside recycling and hundreds more cut back on their programs. Big Waste doubled down and invested hundreds of millions of dollars into costly, high-tech solutions to lower the contamination rate at single-stream facilities. The cost of processing recyclables rose to $120 per ton in many cities. Washington, D.C., now pays an estimated $119 per ton plus a $25 surcharge for processing glass. Despite the premium glass from D.C., which is 20% to 25% of its recycling stream, the material is not recycled.

In the years since China changed its scrap import policies, the U.S. has seen a remarkable turnaround as recyclables were redirected to domestic markets. The private sector has invested billions of dollars into domestic capacity to use paper, plastic, e-scrap and organic materials, and prices for certain commodities have surpassed prior levels in some cases.

Grassroots activists have also succeeded in persuading state legislatures to debate a bevy of new laws: waste surcharges; minimum recycled content; distributed composting; expanded bottle bills, including mandates for refillables; bans on single-use food ware, plastic bags and polystyrene plastic products; mandatory reduction of single-use plastic production; right to repair laws and more. There are now more than 150 local ordinances to limit packaging and increase recycling, with more under discussion.

Some states have also introduced recycling market development agencies, while others expanded the ones they had. Past investment strategies have paid dramatic dividends. Austin, Texas, has grown 6,300 jobs through recycling, composting and reuse and its economy has grown by over $1 billion in the last 10 years as a result — when accounting for multiplier effects.

Contending approaches: Who decides?

The grassroots recycling movement initially asked for “more recycling.” When joined by the anti-incineration movement in the 1980s, which defeated hundreds of planned incinerators, the recycling movement emerged as one focused on zero waste: 90% recycling or more, maximum 10% to landfill, an end to incineration, organics out of landfills and toxics out of packaging.

The National Recycling Coalition, Zero Waste USA and ILSR produced the American Recycling Infrastructure Plan that calls for a 10-year $16 billion investment to build the infrastructure to reach zero waste under the control of states and local government.

Big Waste and Big Packaging think tanks have their own 10-year $17 billion plan for expanding single-stream recycling and a strategy that could lead to a dramatically different future: more incineration via chemical recycling, more direct ownership of processing and manufacturing plants, more virgin plastic production, no container legislation. This would continue a one-way linear economy in a world calling for circularity.

EPR was conceived in the 1990s as a policy based on the polluter pays principle: those who produce waste should pay for its recovery. But by 2013, Nestlé, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, with Big Packaging allies, had weaponized the concept, converting it from a polluter pays to a polluter controls policy: industry in charge and local government, which can be influenced by voters, excluded from decision-making. Heavy lobbying and funding provided to like-minded national environmental organizations led to a torrent of state legislative bills that would give global corporate policies the “force of law.”

Maine and Oregon passed EPR laws in 2021, while California, Washington and Connecticut rejected them. Connecticut’s legislature in particular feared putting too much power in corporate hands. This year, Colorado passed a bill with strong corporate controls through their producer responsibility organizations (PROs) — a monopoly whose decisions will carry the force of law. Maryland recently rejected another bill with a similar model.

EPR discussions in 2022

Colorado’s comprehensive corporate control EPR law goes beyond those in Maine and Oregon, which are considered hybrids with varying levels of corporate hegemony. Proponents reason that incapable government bureaucrats cause the state’s low recycling rate of 10% and 15%, a recalcitrance that can be overcome if industry takes over the system.

Rick Anthony, the former solid waste manager for San Diego County in California — which cut the flow of waste going to its three landfills by 50% in three years — disagrees. “Public servants are the key to efficient recycling. States should tax wasters and use the funds for infrastructure which includes better pay and training for government agency staff,” Anthony said via email recently. Anthony favors democratic control over EPR decision-makers, which is virtually impossible with corporate hegemony.

Clearly, states that have failed recycling systems as in Colorado, are in a quandary as to what to do. Jen Walling, executive director of the Illinois Environmental Council, recently lamented that millions in funding from the state legislature for recycling goes unspent. According to Walling, Illinois agency heads will not even spend $5 million budgeted for recycling.

Should the answer be years of organizing to change the state’s politics? Or is it better to seek a solution with industry that opens the door to forms of incineration, continued reliance on single-stream recycling and long distance transportation of low-value materials and state limitations on local packaging restrictions?

Hawaii’s legislators rejected the polluter-control model and passed a polluter-pay model, EPR legislation with no PRO. Packaging taxes would go directly to the state’s dedicated fund for inclusive distribution to cities and counties. The tax would be imposed on global corporations with $15 billion in sales, not small manufacturers and businesses, and the bill featured a sunset clause after five years. The bill did not get to the governor, due to a feverish wave of lobbying from global corporations.

In New York, there was a complex set of opposing EPR laws this year that didn’t advance before the state’s legislative session ended. A bill proposed by state Sen. Todd Kaminsky would have established a corporate monopoly form of EPR. An opposing bill sponsored by Assemblyman Steve Englebright improved on the Kaminsky bill by requiring mandatory 50% reduction in packaging over five years, with specific targets; all remaining packaging must be compostable, reusable or recyclables. The Assembly bill would have also banned plastic incineration through chemical recycling. The Assembly bill offered a variety of options for forming PROs, but does not require them.

The debates on EPR are important. Assigning responsibility for waste is a critical step to solving the waste dilemma. But who decides?

The choices can lead to a dystopian future of corporate control, continued mediocre recycling rates, markets determined by a few corporations, more incineration of garbage in cement kilns and industrial boilers, a new generation of pyrolysis plants in every population center of the country and more virgin plastic pollution. This would maintain a linear system for an economy and environment that needs circulatory. Or, states and communities can invest in a zero waste infrastructure, as outlined by American Recycling Infrastructure Plan, under the control of local and state government with input from organized citizens, small businesses and the voting public.

EPR is not the problem when the concept includes container deposit legislation and requirements for refillables, as in Europe. It needs to be complemented by minimum content requirements, product bans, waste surcharges and virgin plastic taxes to provide a comprehensive set of packaging policies. It does not need more monopolies. And, decision-making does not need to be removed from the local level.

As we’re seeing with broader discussions in the U.S. right now, democracy matters and the future of individual voices are stake. When it comes to waste and recycling, widespread debate about the actual reality of EPR and its alternatives will determine the outcome of who decides. In making those decisions it's important to keep four principles in mind: Tax what you don’t want, invest in what you do want, ban dangerous materials and vote for champions of zero waste.

Contributed pieces do not reflect an editorial position by Waste Dive.

Do you have an opinion on this issue, or other topics we cover? Submit an op-ed.