Olga Kachook is the director of innovation for the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, a membership organization that’s a project of GreenBlue, a nonprofit dedicated to the sustainable use of materials in society.

As more programs become available across the country and composting facilities launch and expand to meet demand, it’s outdated for anyone to still view food waste recycling as a “West Coast” initiative. 2022 was a strong year for food waste recycling programs, replicating 2021’s growth and continuing a trend of savvy municipalities increasing their focus on food waste diversion programs.

Food waste recycling spreads across the country

This past year, more communities tapped into the environmental benefits and cost-savings potential of food waste diversion with new or expanded residential programs. Composting facilities were often waiting in the wings with increased capacity.

In the Northeast, exciting and long-overdue shifts took place in some of the region’s largest urban areas, including expanded curbside access in New York City and Boston and strong growth in Portland, Maine’s drop-off program. Other programs included Brookline, Massachusetts’ curbside collection service and a drop-off program in Erie County, Pennsylvania, as well as pilots funded through state grants in Meriden and West Haven, Connecticut, to collect material using existing trash carts with separately colored bags.

The state of New York alone, which as of 2022 requires certain commercial generators to donate and recycle food waste, had a notable number of towns and counties enter the food waste recycling conversation, Millcreek, Greene County, Columbia County, Orange County, Philipstown, Beacon, Rhinebeck, and Red Hook all grew residential access to composting programs.

In the Midwest, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Ottawa County, Michigan, Ottertail County, Minnesota, Gahanna, Ohio, Upper Arlington, Ohio, and Madison, Wisconsin, all launched or expanded composting drop-off programs.

Farther south, composting expanded in Charleston County, South Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee, and Bowling Green, Tennessee; Frederick, Maryland, and Prince George's County, Maryland; Richmond, Virginia; and Fort Worth, Texas.

In the West, composting programs are growing despite unique mountainous conditions and transportation distances, in the alpine communities of Snowmass and Telluride, Colorado, Teton County, Wyoming, and Los Alamos County, New Mexico.

So too are facilities expanding to meet demand.

Across the country, at least a dozen facilities grew their operations, retrofitted their processes to accept food waste or break material down more quickly, and experimented with new technologies.

California’s SB 1383 drove facilities to expand in Eureka, Ventura County, Placer County, Yolo County, and across Southern California. Elsewhere, growth and expansion occurred at composting facilities in Stanwood, Washington, Delta County, Colorado, and near Albany, New York, while a new facility opened in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

Atlas Organics, having secured new capital backing for acquisitions in multiple states, expanded into the Pacific Northwest while also introducing unprecedented robotics sorting technology in San Antonio.

Smaller community composting operators also saw exciting growth that may launch them into the midsize operator category: Compost Colorado is building a new facility near Denver, and Compost Crew in the Greater Washington D.C. area raised over $5.5 million in Series A funds.

Humble pilots are often a sign of greater diversion to come

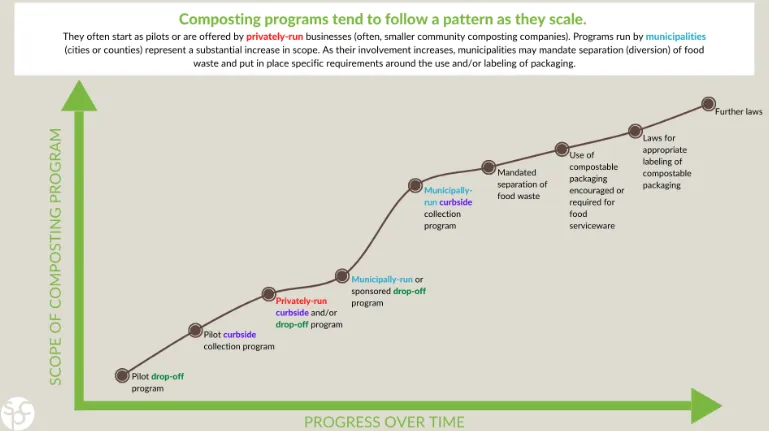

While these programs often start small — accepting material for drop-off only rather than collecting from residents at curbside — this is typically the beginning of a predictable pattern toward scale.

Drop-off pilot programs often become permanent programs run by a municipality, and often pave the way for small-scale, opt-in curbside collection service offered by local community composting companies. As these companies grow, they may begin to engage directly with the municipalities through public-private partnerships.

Residential participation in early, voluntary compost drop-off and privately run curbside collection programs act as strong data points, and can ultimately tip the scales in favor of cities and counties offering their own municipally run, curbside organics collection services on par with their recycling programs.

Importantly, companies need to consider their role in food waste diversion.

2022 continued to show that the necessary programs and facilities are increasingly falling into place, allowing food manufacturing, retail, venues, and restaurants to manage their food waste in a more responsible way. Diverting food waste from landfills is perhaps one of the most straightforward ways for a company to reduce its downstream, previously untackled, emissions.

Any business manufacturing, selling or serving food should be exploring the programs and facilities that may be available, and strongly advocating for these programs if they are not yet in place. Once businesses find a food waste recycling service, front-of-house best practices for how food waste is collected are also beneficial. For example, compostable packaging has been shown in some cases to increase the amount of food scraps that businesses are able to collect and to help reduce contamination of organics.

Food waste recycling is one of the most promising and powerful tools in our collective climate action toolbox, and 2022 has shown that it’s continuing to gain well-deserved traction. We can expect 2023 to bring more news of this trend, as waste management companies and municipalities work together to offer critical food waste recycling solutions.

Contributed pieces do not reflect an editorial position by Waste Dive.

Do you have an opinion on this issue, or other topics we cover? Submit an op-ed.