Von Hernandez's journey in environmental activism began, as so many stories do, on a dark and stormy night. The former literature professor was part of a volunteer rehabilitation group deployed in 1991 to Ormoc City in the central Philippines — where residents were devastated by flash floods brought on by a deadly confluence of Typhoon Thelma, illegal logging and widespread deforestation.

"The night of the disaster, floods came rushing in from the mountains and swept about 8,000 people out to sea," Hernandez told Waste Dive in an interview. "A lot of people perished that night ... For me, that was — shocking doesn't even capture it. It opened my eyes to the consequences of short-sighted decisions, and how people suffer as a result of those actions and decisions."

The experience would prove to be a "key turning point" for Hernandez — he left academia for the global environmental movement, where he's spent the past three decades campaigning on waste and toxics issues worldwide. Previously Greenpeace International's development director, he now serves as coordinator of Break Free From Plastic — a global coalition of organizations advocating for a future free from plastic pollution.

Waste Dive spoke to Hernandez about career milestones, the consequences of transboundary waste dumping in Southeast Asia and the path toward igniting mass systemic change around plastics.

The following conversation has been edited for brevity and annotated for context.

WASTE DIVE: What drew you to Break Free From Plastic?

HERNANDEZ: I've been a waste and toxics campaigner for many years, so this was a natural progression. I've also been involved in mainstreaming "zero waste" work for many years … Often, in implementing such programs, we're confronted with a residual waste fraction — things that cannot be recycled or composted. So the question is, what do you do with them?

That work has, in turn, spotlighted the role of plastics — particularly single-use plastics. We should be compelling manufacturers of such unmanageable components of the waste stream to not produce them in the first place. I think it's only inevitable that we'll have to confront the most problematic components of the waste stream in order to achieve the vision of a "zero waste" society.

You're working on plastics issues now, but one of the things you're most recognized for is an anti-incineration campaign you organized in the mid-'90s — which led the Philippines to pass the world's first nationwide ban on incinerators. What inspired that work?

HERNANDEZ: When I joined Greenpeace in the mid-'90s, one of the earlier campaigns we were focusing on was the dumping of hazardous waste from industrialized to poor countries. We exposed many cases of hazardous waste shipments — from lead waste to mixed rubbish to incinerator ash being dumped from the West to less developed countries.

That, to me, was a clear injustice — and as environmental standards became stricter in the West, we also documented a trend of dirty industries and dirty technologies migrating to the Global South. Like waste, dirty technologies follow the path of least resistance, and the Philippines itself was inundated by a number of proposals to set up incinerators in the mid- to late-'90s. These were being promoted as magic solutions to the landfill crisis we faced in the country back then. We also understood that investing in incinerators meant becoming more of an over-consuming society — thus exacerbating our dependence on the linear model of extraction, consumption and disposal.

So we wanted to turn that around and bring more focus on solutions upstream, or at the front end, to avoid having to deal with disposal problems in the end.

WTE advocates often position incineration as an environmentally preferable alternative to landfilling. How would you respond?

HERNANDEZ: Incineration merely reduces the volume of waste. Burning trash creates toxic ash, which would otherwise still go to the landfill. This toxic ash is not something that you would like to use as soil covering or dump in a landfill. So it actually complicates the problem. Incineration does not get rid of landfilling — even advocates of this technology know it's a volume reduction process.

Much of your current work revolves around the transboundary movement of waste. Can you talk about how China's scrap import policies — and the corresponding shift of exports to developing countries — have impacted Southeast Asia?

HERNANDEZ: We anticipated the influx of waste shipments to Southeast Asia after China adopted the ban. For so long, China tolerated having to deal with mixed waste — with detrimental consequences to the local environment in places where they were processing or dealing with these materials. So China finally said no — they also wanted to deal with growing domestic consumption and, of course, the waste associated with greater affluence.

According to Hernandez, the resulting shift of scrap exports to Southeast Asian countries — the majority of which lack the necessary infrastructure to process mixed plastic waste — transformed communities virtually overnight into waste processing zones and dumpsites.

We believe we've seen the most dramatic examples of this in Indonesia, where an agricultural village has been transformed into a dumping ground almost overnight — people there are now picking garbage instead of harvesting rice or local produce.

And what we've seen is not really recycling, even though most of it is being justified under the guise of recycling or economic recovery. If you were a consumer in the West — in the U.S., for example — you would think you're doing the right thing by segregating your trash and putting recyclables in the right bin. But actually, you never realize your so-called recyclables are being exported to places where there are loose controls and even less capacity to handle such materials.

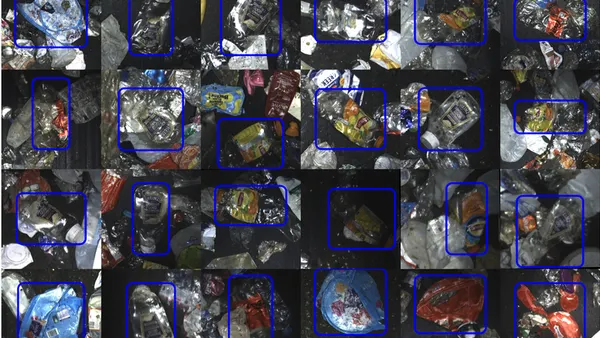

Hernandez talks about the "minimal" extractable value of the bulk of Southeast Asian scrap imports, noting that many shipments classified as pellets or plastic flakes are, in fact, containers filled with mixed plastic waste.

That's why a lot of such shipments end up being dumped — and not even in proper landfills, mind you, but out in the open. There's also a lot of open burning, as we've seen in Indonesia, where locals end up using the unrecyclable plastics as fuel to prepare tofu. It's shocking to imagine all those toxic emissions ending up in food. These are images you won't find, I think, in Europe or Australia or the U.S. — but they're becoming more prevalent in Southeast Asia as a result of the China ban.

Some governments are pushing back against this shift — Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, among other countries, have banned further scrap imports. Do you think it's enough, or do we need even more radical action?

HERNANDEZ: Well, local communities in these countries are being agitated, of course, being at the receiving end of these waste shipments. They feel the effects on their health, and that has galvanized communities to pressure their governments to take action. In Malaysia's case, you'd think — being relatively wealthier — they'd be more capable than other Southeast Asian countries of handling the waste materials in a responsible manner. But even they can't properly regulate all the fly-by-night recycling operators that have suddenly sprung into place. The Malaysian government did the right thing by declaring a ban, suspending imports and now deciding to return the waste shipments to their countries of origin.

That's also why the recent decision adopted by the Basel Convention is important — it gives receiving countries the power to say no to plastic waste shipments before they come in, with the Basel Convention amendment, at least countries will have to give their consent before those shipments are sent over.

However, it will be a year before the amendment takes effect — which means we have to guard against the onslaught of plastic waste shipments trying to beat the deadline.

Journalist Adam Minter has pushed back against what he refers to as the "myth" of waste dumping — he argues that if material is moving to a country, it must be because someone there sees its value and is willing to purchase it. How would you respond?

HERNANDEZ: Minter should visit the dumping sites in Indonesia and see for himself whether these materials are really being recovered. You could burn mixed plastics to cook your tofu, like the Indonesians are doing in North Sumengko. Is that something Minter would find useful? If the material was so valuable in the first place, you would think more capable countries, industrialized countries, would be able to find innovative ways of dealing with it — ways that do not create pollution.

The fact is, these so-called recyclables are coming in as mixed waste. If they were coming in as, say, industrial scrap or homogenous materials, then maybe there would be an argument for processing them or dealing with them in an environmentally responsible manner. But mixed waste exports translate to outright dumping. If Minter is convinced that these are valuable materials being exported, he should be making his case to the source countries to recover and be responsible for these exports. Maybe dealing with it back home is the responsible thing to do.

What this episode exposes is the bankruptcy of the recycling argument. For years, we've been conditioned to believe this plastic waste can be properly recycled, and now we're seeing on the ground what a fallacy this has all been. While there's a bit of recycling going on — downcycling is actually the more accurate term to describe it — it is not the cradle-to-cradle recycling that should be consistent with our vision of a circular economy. This kind of recycling is simply suspending the inevitable — but even in this case, we're not doing that properly, as the discards go straight to the dumping ground or are burned openly.

To solve the plastic pollution crisis, we need to focus upstream. We need to stem production. We need to compel the industry and the manufacturers to go into cradle-to-cradle recycling. They need to be responsible for the materials they are deploying into the market.

What do you think is the most effective way of compelling industry to take responsibility?

HERNANDEZ: The real solution is to reduce the amount of plastic waste being generated. In order to compel companies to improve recycling efficiencies and do away with unnecessary packaging, we would need to mainstream and legislate clean production approaches. Governments and cities would need to invest in front-end solutions, even come up with really strict segregation practices. I know the best recyclers in the U.S. do what they can to improve segregation, utilize mechanical recycling and all that. But certainly, there's room for improvement. The kind of plastic waste currently being exported to the Global South simply does not allow for responsible and more efficient recycling to take place.

Then there's the question of moving upstream and eliminating problematic chemicals and toxics in materials to make it a cleaner process down the line. It would take a combination of measures — it's not enough, for example, to adopt simple extended producer responsibility measures, because if companies were responsible for collection, they would probably just come up with the most convenient way of exporting or disposing of the problem.

What do you think of plastic bans?

HERNANDEZ: Definitely needed as a plastics reduction measure. We're seeing more and more countries, cities and jurisdictions coming up with ways to reduce their plastic footprint. Bans would be one of the most effective approaches — because they also compel retailers and consumers to think of better alternatives. If you have a crisis, you must look at options that avoid contributing to that crisis. Maybe there are alternatives, or maybe there are other methods for delivering the product that don't create so many problems down the line.

This is the innovation and creativity challenge we're posing to industry. Most corporations are so invested in this business model of single-use plastic packaging that they're even projecting future growth based on this framework. Companies need to start thinking outside of this model and see how goods could still be effectively delivered to the market without the associated problems we're finding with throwaway packaging. Moreover, we're becoming more aware of the human health and climate impacts of plastics throughout its supply chain — from production to use to disposal.

Looking back on your career, what are you proudest of?

HERNANDEZ: Mostly, I'm proudest of the network of organizations and alliances we've built over the years ... In the past, one looked at plastics pollution as simply a waste management issue. But now, we have communities campaigning at the frontlines of the petrochemical buildup. We're working with organizations that are concerned with toxics coming out of plastic food contact materials. We're working with groups concerned about waste dumping and marine pollution. Having all these groups working together and being part of the movement that's making it happen is both validating and energizing.

What's next for you?

HERNANDEZ: Well, we will continue what we've started. There's so much momentum riding on this issue. We'll keep talking with governments to address policy gaps, we'll continue to engage with companies and try to convince them to shift their practices. This will probably take a little more time, so we will continue to work at it.

And are you optimistic about the rate of progress? It can be difficult, when contemplating the effects of climate change and environmental degradation, to see what hope there is. But are you hopeful?

HERNANDEZ: Yes. We have to be hopeful. There are signs of progress. There are also signs of, of course, pushback, and we have to deal with that. We are taking on capitalist greed as we try to reverse all these trends that are undermining our future. So, yes, we have to be optimistic. We see optimism in positive government action on plastics. The recent Basel Convention amendment is part of that. It will be an uphill battle, but I'm confident we will eventually change it. We will turn the tide.