Interest in solar energy continues to heat up, with solar panel installation growing in the past few years. That growth is likely to further intensify thanks to a boom in clean energy project interest and funding. The uptick raises a key question: What happens to all those panels when they reach the end of their lifespans?

Solar panel recycling is still in its infancy, and launching collection and reuse programs isn’t a simple task. Challenges include the presence of potentially hazardous materials, a high cost to recycle and low commodity values.

"Solar, wind and batteries all are expected to play a major role in meeting climate change goals because they’re sustainable resources. But, ironically, the recycling infrastructure is woefully inadequate to address the types of products coming off of those projects," said Kelly Sarber, CEO at environmental consulting company Strategic Management Group.

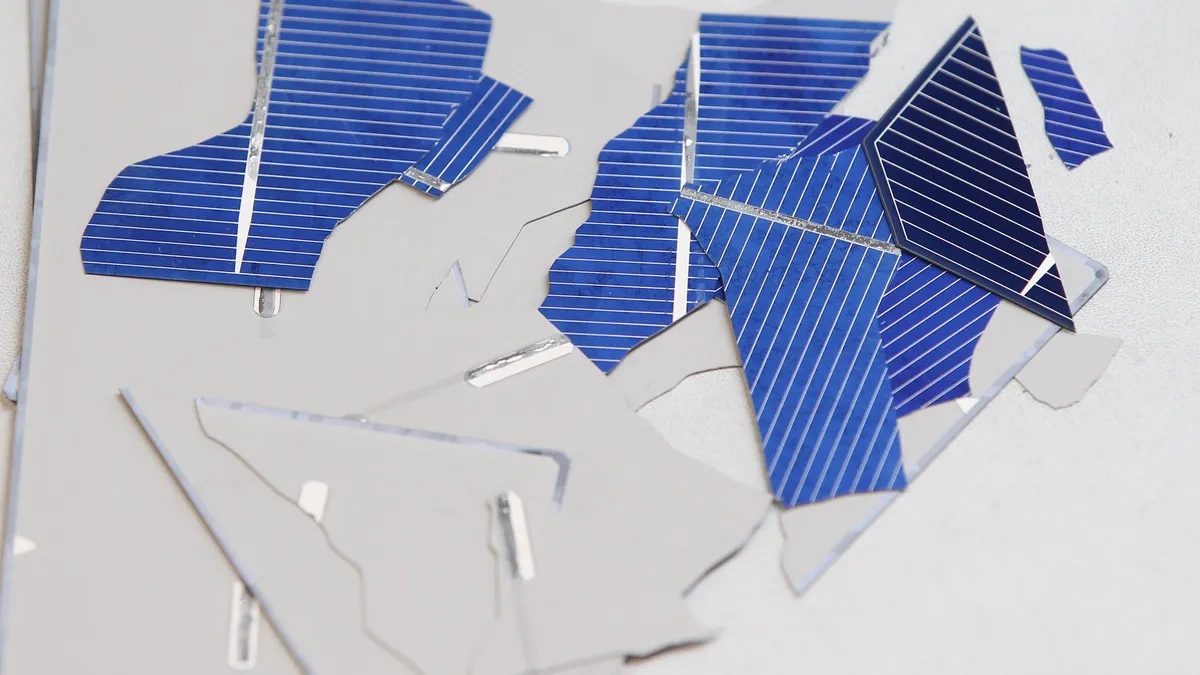

Solar panels are so bulky that even one installation is a big deal at the time of disposal, let alone when you multiply that by hundreds or thousands for commercial-scale arrays. Solar cells generally have an estimated 20- to 25-year lifespan, and the vast majority were only installed in the last decade, but they frequently get replaced sooner. Like all products, they can prematurely stop functioning or can fail when damaged — an event like a hailstorm can take out thousands of cells at a utility-scale array. Reports of energy efficiency losses over time in older cells also are another factor prompting upgrades to newer, smaller, lighter, more powerful panels.

"As efficiency improves on a smaller footprint, there will be financial pressure to replace panels because the new ones generate that much more power," Sarber said.

The challenges with end-of-life solar technologies are increasing calls for manufacturers to better adhere to design-for-recycling practices. And as solar panel designs and materials evolve, so do the recycling methods and industry participants. For example, Sarber anticipates flat screen TV recyclers might delve into solar cell recycling because the processes have similarities. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory is among the entities advancing new repair, reuse and recycling techniques and technologies that align with circular economy principles.

The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) also promotes and works to develop solar panel recycling. SEIA members can participate in industry-based takeback and recycling programs, and SEIA's PV Recycling Working Group says it actively seeks and develops recycling partners across the country. The organization contends that aggregating solar manufacturers' and recyclers' services leads to more cost-effective and environmentally responsible end-of-life management.

Some state and local governments are tackling the disposal issue and drawing up legislation dictating what happens to retired solar cells. In the meantime, recyclers, researchers, industry groups and solar panel producers continue working on ways to responsibly reuse the devices or their components.

"The industry has what I think is a lot of foresight to try to figure out and build out capacity for the end-of-life panels before it actually becomes a problem," said Corey Dehmey, executive director at nonprofit Sustainable Electronics Recycling International (SERI), which manages the R2 recycling certification standard for electronics recyclers. "We’re aware of a number of R2 recyclers who for years have received solar panels. Going back as far as 10 years ago, solar panels were coming through in trickles. The volume is continuing to pick up."

Are solar panels the 'new CRT'?

Solar panels present challenges that lead waste and recycling industry participants to dub the devices the "new CRT," referencing the mountain of issues that end-of-life cathode-ray tube TVs posed once the materials they contained were no longer in demand by TV and monitor manufacturers.

For instance, different solar cell designs contain materials — including lead, cadmium, arsenic, selenium and chromium — that could be hazardous if not recycled or disposed properly. This is reminiscent of lead in CRTs posing a a hazard when abandoned or landfilled, or not recycled safely.

If proper legislation and stewardship programs are not put in place prior to panels entering the waste stream en masse, the industry could face a similar crisis, said Robin Ingenthron, CEO of Vermont-based Good Point Recycling and founder of Fair Trade Recycling. He contends that solar cells, like CRTs, have reuse value but could be improperly deemed hazardous waste through regulation devised by misinformed parties.

"What we're concerned about right now is that we not repeat the mistakes of the ‘war on reuse’ that happened 20 years ago," Ingenthron said.

Good Point Recycling is launching a fair-trade pilot project through which it hopes to demonstrate a viable, ethical future for solar panel repair and reuse. Solar cells that still function will be sent to emerging markets, such as Ghana and other African countries. Project partners promise that the "reuse first" model can lower the cost of recycling infrastructure while providing data that serves as a guide when devising regulations.

"What we’re trying to do with our pilot is more aggressively get the facts out about solar panels before people start making wrong assumptions," Ingenthron said. "Right now, the only people we’re seeing who have a lot of interest in buying them are from the tech sector, not the scrap sector."

Some original product manufacturers worry about reuse programs causing market cannibalization, he said, but reuse markets are different from equipment manufacturers' first-round markets.

“These are reused in markets they’re not selling into… It would be decades before they sell to an African hospital, for example,” Ingenthron said. “That's kind of my expertise: using used equipment to develop infrastructure in emerging markets. We hope to convince the industry that it’s a win-win.”

Another parallel to CRTs commonly cited by Sarber and other experts is the lack of profitable markets for reclaimed solar panel materials.

"There is a real gap between the cost to recycle solar panels and the value of the materials that you’re deriving from that process. It’s cheaper to dispose of the products in landfills," Sarber said.

Most of the value lies in the aluminum frames, and some also comes from copper, silver and silicon in components like wires, circuitry and glass. It costs $20-30 to recycle each panel, whereas they each might only contain $3-4 of reusable and marketable material, Sarber said. That total could be even less for newer models that are smaller, lighter weight and contain fewer metals.

“Recycling the materials for their commodity value is a losing proposition today… The market structure doesn't support recycling without incentives or product stewardship,” Sarber said. “What we see happening now is building capacity to repurpose and recycle these materials, but it’s not in an organized fashion and done around regulations.”

Policy approach

The United States lags other areas in end-of-life solar panel regulation. For example, the European Union regulates solar panel recycling and mandates manufacturer stewardship, requiring 85% collection and 80% recycling of the cells' materials. Many countries that support the Basel Convention (of which the U.S. is currently not a signatory) also consider end-of-life solar panels and other electronics hazardous waste to be in the banned hazardous waste category.

A handful of U.S. states are exploring product stewardship legislation for the panels. New Jersey passed a law in 2019 establishing a solar panel recycling commission to investigate end-of-life management with a report expected by next year. In 2020, California finalized regulations making solar panels universal waste – not hazardous waste – to ease collection and transportation burdens. New York state is investigating similar universal waste regulations. Last month, Niagara County, New York, became the nation's first local government to pass a law requiring producer responsibility for solar panel recycling.

Washington state led the pack with a 2017 law requiring solar panel manufacturers to finance takeback and recycling. It requires any solar panel suppliers who sell products in the state that were manufactured in July 2017 or later to participate in the industry-funded stewardship program.

Legislators and regulators are still working out some specifics, including the exact amount of solar cell material that must be recycled and details regarding rare earth mineral handling. They're also tweaking stewardship program logistics, such as collection site locations and whether solar installers would be part of the collection process.

"Do you really need one collection site in every county for this product? Probably not," said Al Salvi, technical services unit supervisor in solid waste at Washington's Department of Ecology. "We’re working with industry a lot to figure out what works best."

The original law was supposed to be implemented this month, but bill changes in subsequent legislative sessions have pushed back implementation to 2025.

Salvi says some solar industry players pushed unsuccessfully to incorporate language that would have added an environmental handling fee to consumers’ costs, in addition to other proposed changes that would have alleviated at least some manufacturer onus for responsible disposal.

"This is something that needs to be funded by manufacturers. If you’re a homeowner, you shouldn’t have to pay to enter this program," Salvi said.

Proper product handling concerns prompted SERI to consider adding solar panels to the R2 certification standard. The organization’s technical advisory committee voted this spring to begin the long process, which involves soliciting stakeholder input, writing multiple drafts and incorporating feedback into subsequent drafts. Dehmey said "we're years away" from certifying solar panel recyclers or specifying the operational requirements for certification. If everything stays on schedule, a first draft of solar panel recycling certification requirements could be drawn up by the first half of 2024.

"This will help identify environmentally sound practices for handling solar panels and will recognize facilities meeting those practices. It's easy for everyone to say they’re doing it the right way, but how else would we really know?" he said.

Sarber said, however, that as solar panel recycling evolves, it must include steps to ensure hazardous electronic material doesn’t simply get exported to regions with less stringent worker safety and environmental regulations.

“There are tremendous financial incentives to invest in this burgeoning recycling space due to the massive amounts of products expected to hit the market," she said, "but the infrastructure is still nascent, and creating a circular economy is going to involve having a focus on product stewardship, regulatory enforcement and industry commitment to ESG goals."