Dive Brief:

- Medical care is increasingly moving away from hospital settings and into homes. That’s changing waste streams in ways that will affect both MRFs and healthcare workers, said speakers during a healthcare waste panel at WasteExpo, held May 5-8 in Las Vegas.

- Better access to injectable medications, as well as “hospital at home” services to recover from procedures that once required longer hospital stays, are other factors adding to the trend.

- Diverting that waste away from MRFs is a challenge, but could improve with more robust takeback networks, producer responsibility programs and patient education, speakers said.

Dive Insight:

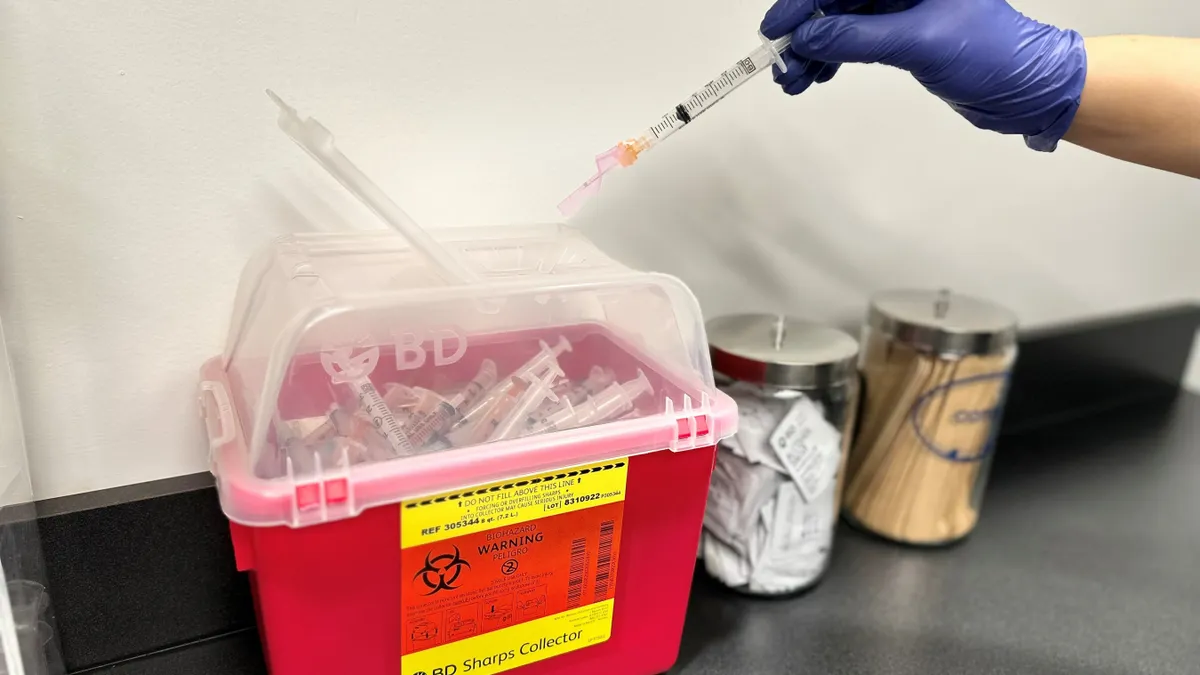

Keeping healthcare waste out of household waste streams is an important safety measure to prevent needlestick injuries, exposure to hazardous waste pharmaceuticals and battery fires at waste and recycling facilities. It’s long been a challenge to reduce worker exposure, waste industry experts say.

Hospitals generate about 42 pounds of waste per hospital patient per day, and a “small percentage” of that is regulated medical waste and pharmaceutical waste, said Kristin Aldred, director of government affairs at Stericycle. Over the next few years, “about 30% of what happens in hospitals today could take place in the home,” shifting some of that volume to residential streams.

States have a range of laws that regulate the proper disposal of medical waste in residential streams, but it can be tough to know what’s required from state to state, especially for home healthcare workers and people tasked with caring for a family member at home, said Elise Paeffgen, environmental partner at Alston & Bird who specializes in waste topics in the healthcare industry.

These patients may also have their medications, medical sharps and even battery-containing medical devices mailed to their homes. That means it’s more likely that material will end up in curbside streams when patients are not sure of the proper disposal method, speakers said.

“A lot of state medical waste regulations were put in place years and years ago, before there was a lot of healthcare services provided in the home. That makes this significantly more challenging today,” Paeffgen said.

States including California, Oregon, Wisconsin and Massachusetts have banned the disposal of containerized sharps in residential waste, according to a MRF sharps study from the Environmental Research and Education Foundation. Other states exempt sharps generated in the home from landfill bans, and a another set of states does not say if their disposal regulations cover medical sharps generated in homes, Paeffgen said.

Even when households understand how to properly dispose of medical waste, they often lack access to disposal sites, said Hanz Atia, a policy and programs associate at the Product Stewardship Institute.

Citing the EREF study, Atia said up to 95% of household sharps are discarded “loose and unprotected in the municipal waste stream.” That’s an estimated 3 billion sharps a year.

PSI advocates for extended producer responsibility programs for numerous materials, including pharmaceuticals and medical sharps. So far, only California has a producer responsibility law for medical sharps, but Atia said PSI continues working with stakeholders across the country to advance other legislation.

In the meantime, numerous groups and agencies are working on programs, such as voluntary state and local takebacks, to fill major gaps in collection infrastructure, she said.

PSI partnered with the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality in 2022 on a six-month sharps disposal pilot that covered five sites throughout the state. A year later, the state received an EPA grant to continue running those collection sites as well as expand to 15 other locations run by the Choctaw Nation, Indian Health Services and Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

Today, Atia says the state has 49 permanent collection sites and runs additional take-back events throughout the year. In 2024, the program collected over 1,800 pounds of medical sharps from nine different take-back events, she said.

Efforts are also underway to keep pharmaceuticals from disposal. These products might be less of a safety hazard for MRFs compared with medical sharps, but are still considered contamination in waste streams, she said.

Proper disposal can also reduce incidences of accidental ingestion, especially by children, and help prevent opioid abuse, Atia said. At the national level, the Food and Drug Administration now requires certain opioid manufacturers to provide prepaid mail-back envelopes for patients when they pick up the drugs at pharmacies. That program launched March 31.

At the state level, eight states also have some kind of product stewardship law for pharmaceuticals, according to PSI.

Disclosure: Informa, which owns a controlling stake in Informa TechTarget, the publisher behind Waste Dive, is also the owner of WasteExpo. Informa has no influence over Waste Dive's coverage.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify state laws and policies on sharps medical waste generated at home.