Dive Brief:

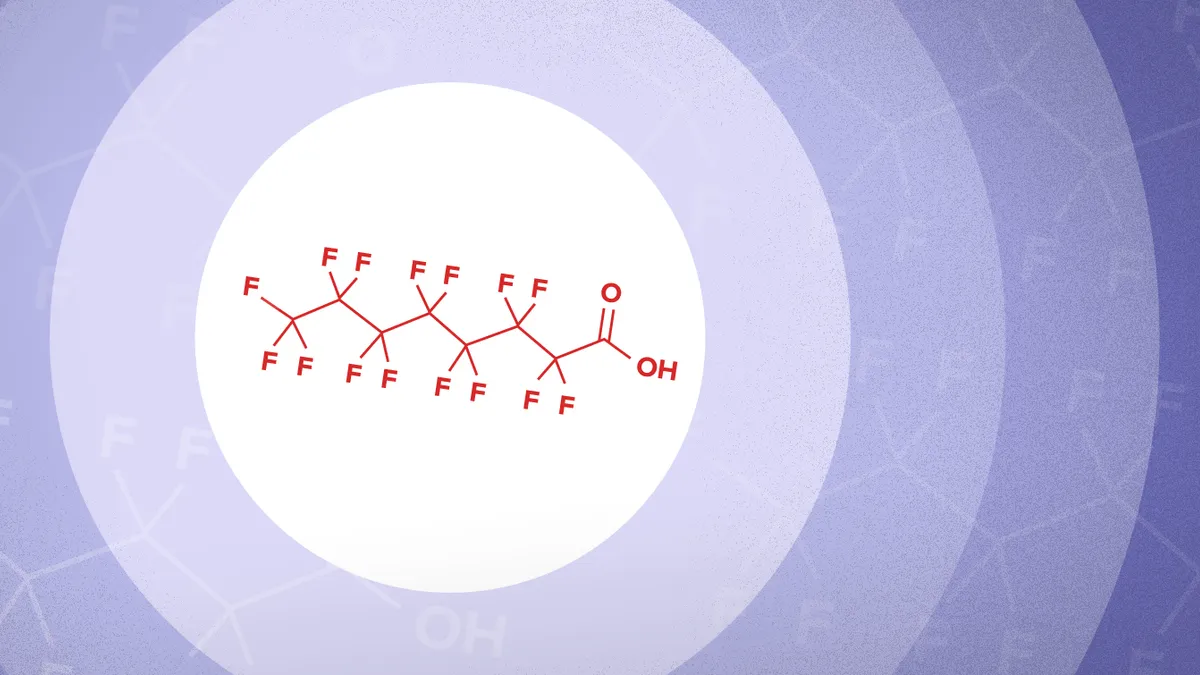

- The U.S. EPA announced the PFAS Strategic Roadmap on Monday to address contamination from PFAS, setting a 2023 final rule deadline to regulate PFOS and PFOA in drinking water and designate the two compounds as hazardous substances. It also pledges to do more research and testing on hundreds of other PFAS, meaning it could deem other PFAS compounds as hazardous substances in the future.

- The three-year action plan also pledges to provide updated research by fall of 2023 on the available methods for disposing of or destroying PFAS through landfills, thermal treatment and deep-well injection.

- The road map lays out timelines for other research and development efforts meant to learn more about how PFAS impacts communities and the environment. “We need to gain a stronger and more complete science-based understanding of the problem, so we can put in place durable solutions that keep people healthy," EPA Administrator Michael Regan said during an event announcing the road map.

Dive Insight:

Landfill operators have long expected the EPA to regulate certain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) but have felt stuck while waiting for concrete dates that could help them plan for future operational changes. The PFAS Strategic Roadmap offers a more complete timeline than before, but some waste and recycling players worry the three-year plan doesn't provide enough of a complete picture to begin preparations.

Environmentalists and waste and recycling industry stakeholders are split on the plan. Some expressed cautious optimism that the road map reflects the Biden administration's pledge to make PFAS a priority and sets specific deadlines to achieve ambitious regulatory and research goals. Others are concerned that the road map does not enact meaningful changes quickly enough or does not hold polluters appropriately accountable. Groups such as the National Resources Defense Council (NDRC) pointed to the PFAS Action Act, which passed the House in July, as containing a faster implementation timeline and stricter provisions than the EPA's road map.

Many in the industry see hazardous substance designations as important steps in managing PFAS, but some landfill and incineration operators may try to reduce their regulatory risk in the near future by choosing contracts where there's less of a chance the materials contain PFAS, predicted David Biderman, CEO of the Solid Waste Association of North America. The concern lies in managing materials that may include PFAS compounds not yet listed as hazardous substances, he said.

“It will create some challenges and concerns in the marketplace,” he said. “It’s not just the PFAS that is already in the garbage. There may be other projects a landfill may not decide to do because of the regulatory uncertainty. Today a material is not [designated] as hazardous, but perhaps in 2023 or 2024 it will be, and then what happens?”

Biderman also thinks this could prompt increased disposal costs as landfills budget for complying with new regulations for aspects such as leachate management. Landfills “may also need to set money aside in the event that they become part of Superfund litigation,” he said.

Yet some waste companies view future EPA regulations as a possible business opportunity to manage PFAS-containing materials.

The EPA has little data on the toxicity of numerous individual PFAS. The road map includes plans to further evaluate “a large number” of these PFAS for possible human health and environmental effects, it states. In the meantime, the agency will release toxicity assessments for more well-known ones such as Gen X and five other PFAS in the coming weeks, according to the report.

As the EPA gains a better understanding of specific PFAS compounds, it’s unclear whether it will regulate the rest of PFAS together as a class, or take a piece-by-piece approach by regulating smaller groups of compounds with similar properties or health impacts together.

Advocates for regulating PFAS as an entire group say the compounds are so numerous that it could take too long for the EPA to analyze and place each one in a subcategory, leaving communities vulnerable to exposure while they wait for EPA action.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility expressed frustration at what it called the road map’s “whack-a-mole” approach to developing toxicity standards for only a handful of compounds and focusing regulatory limits only on PFOS and PFOA.

Betsy Southerland, former director of science and technology in EPA’s Office of Water, said the agency must work swiftly to "group an enormous number of chemicals into as few categories as possible" in order to streamline future regulations. "This will accelerate the bans and restriction of use," she said.

Yet the chemical industry and groups such as the American Chemistry Council have called for the EPA to regulate multiple types of PFAS together in smaller groups that have similar chemical properties or health impacts, saying that all PFAS are not the same and shouldn’t be regulated as such.

The road map also promises to deliver an updated version of its PFAS disposal and destruction guidance, which highlighted the available science behind using deep well injection, landfilling and thermal treatment, ranking them in order of perceived safety and viability. That report, released last December, noted that more research is needed to help guide future policy decisions. The EPA anticipates more destruction and disposal research data will come out in 2022 and update guidance no later than December 2023.

More specific insight from the EPA on how best to manage PFAS-containing items that come to landfills and incinerators will be critical as the agency also moves to regulate more PFAS as hazardous substances, Southerland said. As more PFAS-containing items are banned or restricted, “it will create more and more need to dispose of it safely, so this EPA research on disposal will be very important.”

The road map also mentions manufacturers’ role in reducing PFAS contamination, including requiring PFAS manufacturers to pay for some EPA research. Brandon Wright, vice president of communications for the National Waste & Recycling Association, said this focus is important for the waste industry. “We’re receivers of PFAS, not creators. As we have said to the EPA before, the burden needs to be shifted back to manufacturers that are using PFAS.”

During a speech unveiling the road map on Monday, Regan emphasized that the agency is committed to working speedily on checking off each item on the plan’s list and holding polluters accountable, but some environmentalists say the message comes too late.

The NRDC, frustrated with slow movement on PFAS action during the previous administration, said the EPA should do more to regulate the chemical industry as a polluter. The road map “contains some potentially positive steps forward, but the plans announced are not enough, or fast enough, to tackle the ongoing PFAS crisis,” said Daniel Rosenberg, NRDC’s federal toxics policy director.

In the spring of 2022, the EPA plans to seek public comment on its proposed rulemaking to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances. It may separately seek public comment on whether to designate certain other PFAS as hazardous substances around that same time. EPA expects to issue a proposed regulation in Fall 2022 for PFOA and PFOS limits in drinking water, with the final version coming in 2023.