Dive Brief:

- A recent "state of the science" report from the U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development calls for more research on PFAS in compost and digestate, saying there are currently too many unknowns about how the chemicals show up in such material. The report, meant “to inform food waste management decisions," compiles the available research on PFAS and other chemical contamination found in food waste, hay and manure used for compost and anaerobic digestion.

- Composts made from a variety of materials have a range of different contamination levels, the report said. Biosolids are thought to have the highest concentration of PFAS, followed by food waste, then yard waste, according to the report. Both the EPA and organics experts say a major source of PFAS in compost comes from packaging.

- Organics and compost trade groups say the report unfairly scrutinizes their sector and mischaracterizes some of the data in the report. More should be done to target PFAS manufacturers and manufacturers of packaging and products known to contain the chemicals instead, said Frank Franciosi, executive director of the US Composting Council.

Dive Insight:

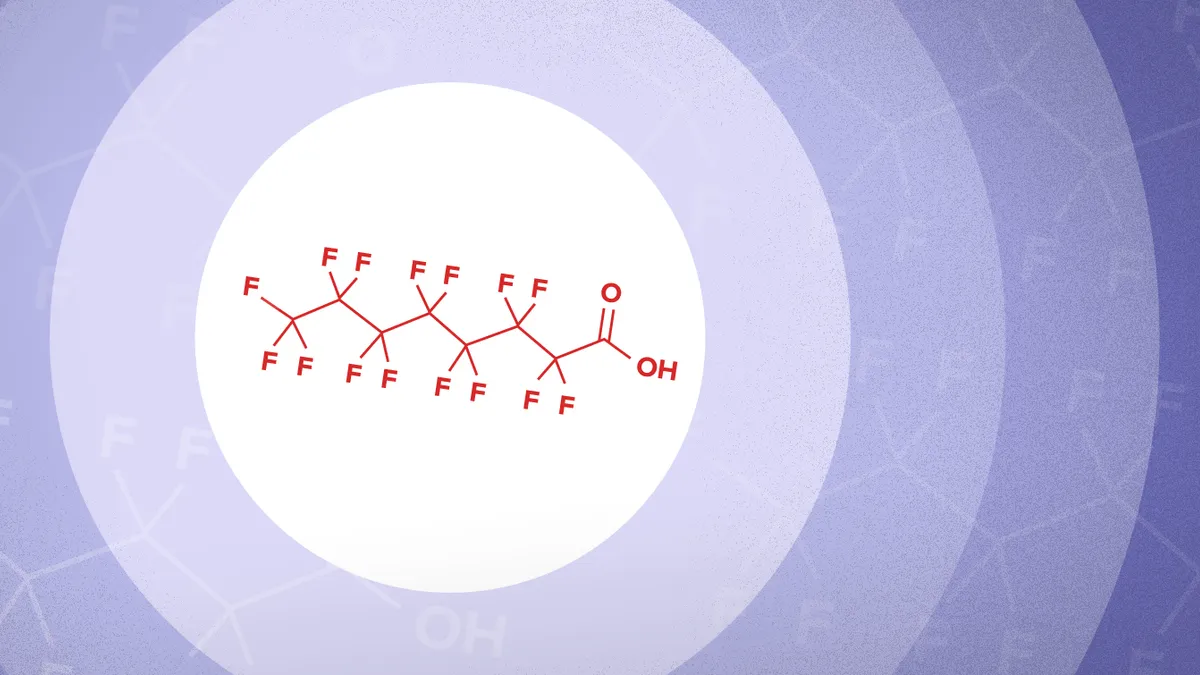

It’s well-known that compost and biosolids may contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and experts have been grappling with how to handle the contamination while they await state, local and federal rules they hope will curb the substances in the future. Composters say the report highlights what they already know: that available information isn’t enough to offer a complete picture of the problem, and that companies and lawmakers need to do their part to mitigate such chemicals while scientists conduct more research.

“This issue is created by the companies that created these forever chemicals. Food has some PFAS in it, but the report also shows that it can show up anywhere, so how do we control that? It’s not something we have an easy answer for,” Franciosi said. “Our position is, let’s follow the stream of where the [PFAS] started and go upstream first. We need to fix upstream problems while we also get some more science behind this.”

The EPA says it encourages food waste recycling because it reduces landfill methane emissions and helps the agency reach its goal to cut food loss and waste in half by 2030, but its report also states concerns over unknowns related to compost contaminants, such as PFAS, plastics and pesticides. The EPA has also released a separate report about plastic contamination in compost.

The report says different types of PFAS contamination may have different health and environmental effects. When present in biosolids, the report says, “PFAS can be taken up by plants and crops and/or leach into groundwater, which can be consumed by people and animals or used for agriculture.” However, the EPA could not gather enough data from the “available literature” to determine the effects of contamination in compost and digestate made from food waste streams.

Composters that handle food waste think the main source of PFAS in their facilities is packaging waste, and the EPA report highlights one study showing that PFAS concentrations were higher in composts that included compostable food packaging than those without. However, the EPA acknowledges there’s “limited data” on the topic.

The Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), which certifies items including biodegradable packaging, disagrees with how the EPA characterized the study comparing composts with and without compostable food packaging.

“The study was about municipal organic waste streams that have food packaging more broadly, not specifically compostable packaging,” said Rhodes Yepsen, BPI's executive director, in an email. "This is an important distinction, as only a fraction of food packaging is certified compostable today, and only one material type of certified compostable items (molded fiber) ever had PFAS, with other items using compostable biopolymers to provide grease and moisture barriers.”

In 2020, BPI stopped certifying compostable food packaging known to contain PFAS, a move the EPA report says “should lead to decreased PFAS levels in food waste streams.” Some composters have said they will not accept compostable food packaging.

Sally Brown, a research professor at the University of Washington's School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, said the report misses the mark on the important steps needed to reduce and eliminate PFAS in the environment. She argues that more needs to be done to eliminate PFAS at the source instead of starting with compost.

The EPA has not yet responded to a request for comment.

Some PFAS chemicals, such as PFOA, are no longer used in the United States to make certain items like fire-resistant products, and United Nations regulators voted to ban PFOA in 2019. Brown said restrictions on such PFAS chemicals have led to lower concentrations in human blood levels, “so it really does work to ban the compounds,” she said. However, other PFAS chemicals are still being used in everyday products such as cosmetics. “It’s a real question of if they’re necessary. How much would your lipstick suffer if it wasn’t in there?” she said.

Some manufacturers are voluntarily phasing out particular PFAS from food packaging. In January, McDonalds announced it would remove all PFAS-containing packaging by 2025. The company estimates 7.5% of its packaging globally still contains added fluorinated compounds.

There are currently no standards for PFAS in finished composts or digestates, but the EPA report mentions that state and local guidelines prohibiting PFAS in food packaging have gained momentum in recent years.

Maine, Vermont, Connecticut and Minnesota passed laws this year banning or phasing out packaging containing PFAS. New York and Washington also have similar laws. When signing his state law in July, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont said minimizing future releases of PFAS to the environment is an important way to protect people from the health risks posed by PFAS.

At the federal level, lawmakers are also working to advance the PFAS Action Act, which would set a deadline for the EPA to designate certain PFAS as hazardous substances and place a moratorium on products containing new PFAS. Some lawmakers have urged the EPA to speed up its regulatory process to avoid a “patchwork of regulations” they say could create confusion or uneven environmental protections.

Though PFAS is one of the EPA’s major compost contamination worries, the report also compiles information on contamination from other sources, such as persistent herbicides. It says food waste is not a major source of these herbicides in compost, but leaves, grass and manure present a higher risk of introducing these chemicals.