As the waste and recycling industry increasingly faces environmental justice considerations, the regulatory definitions that underpin this discussion can vary state-by-state — both in terminology and scope.

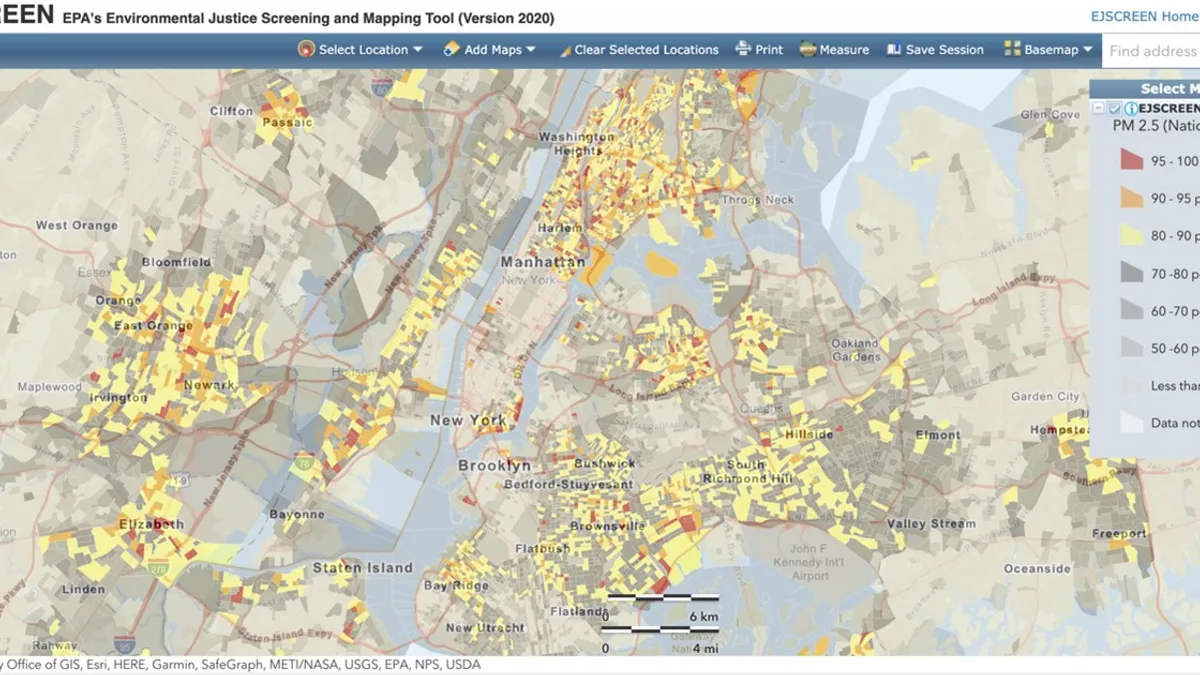

The federal government has made some efforts to standardize definitions and initiatives across the board. The U.S. EPA released EJScreen, a geospatial tool to search demographic information on “environmental justice communities,” in 2015. Most recently, the Biden administration has announced the Justice40 initiative, which aims to distribute 40% of benefits from federal investments to “disadvantaged communities.”

In 2021, at least 150 bills were introduced across state legislatures relating to environmental justice. Some states, like New York, have had language around environmental justice since the 1980s. Others have come later, or made updates to their policies. As of 2021, Bloomberg Law reported that 10 states had codified environmental justice legislation, with another 13 pending. Following the relevant definitions and standards in a service provider’s operating region has become increasingly important amid this trend.

State approaches

Though the concept of environmental justice is used across different legislation and permitting requirements, the way communities are specifically identified and addressed varies, as does the degree of implementation. Specifically, the language around how communities are named varies, as does the criteria to be categorized as such.

Massachusetts, for example, defines “environmental justice populations” by meeting one of four criteria. In contrast, New Jersey names these populations as “overburdened communities.” California, on the other hand, defines them as “disadvantaged communities” through SB 535 and SB 350, which ensures additional funding for the communities through the energy transition.

Massachusetts’ target populations are typically constrained to the neighborhood level, though the availability of data is rarely that granular. In order to qualify, the area must meet at least one of three criteria, including a certain annual household income threshold, demographic composition, and English language proficiency. Communities can still be designated as environmental justice communities if they do not meet these criteria through two exceptions, including the state government designating a portion of the neighborhood as such.

New Jersey’s geographical constraint is a census block group. In order to fit the definition, communities must meet all three criteria of low-income percentages, demographic compositions, and English language proficiency. New Jersey’s criteria are parallel to those in Massachusetts, but their income criteria are based on federal definitions of the poverty line — not the state median — and the community must meet all of the criteria, not one or more.

California has four categories of geographic areas qualifying as disadvantaged. These areas are tied directly to CalEnviroScreen, a geospatial tool used to identify communities that are most likely to be impacted by, or are already impacted by, pollution. Two designations for disadvantaged communities correspond to the score calculated by the tool for the census tract; the other two relate to a 2017 “disadvantaged community” designation, regardless of CalEnviroScreen results, and any lands under the control of federally recognized tribes.

Just within these three states, there are several similarities and differences in how targeted populations are named and defined. “The lack of standards will make it hard for there to be industry ‘best practices’,” said Matthew Karmel, an attorney at Offit Kurman who heads the firm’s environmental and sustainability law practice. He classified two issues when it comes to defining the communities: terminology and context, and how they match up with one another.

This lack of standardized definition from a legal perspective can be used against advocates at times, according to Byron Chan, senior attorney at Earthjustice.

“Oftentimes, you’ll be in a proceeding where you’ll say, ‘This power plant is being sited in a disadvantaged community’, and the agency who is proposing the power plant will say, ‘That disadvantaged community designation is about funding under SB 350, which has nothing to do with how we are going to define environmental justice community,’” he said.

For some non-governmental organizations, like the California Environmental Justice Alliance, terms like disadvantaged, environmental justice and marginalized can be used interchangeably. Their preference for the statute is in line with California’s “disadvantaged community” nomenclature.

The California legislation is often helpful, especially because of the continuously evolving CalEnviroScreen tool, according to Raquel Mason, policy manager at the California Environmental Justice Alliance. “We really want to preserve [CalEnviroScreen] as a tool. It it helps tell the stories that the communities we work with already know and really raise them up in policy,” she said.

Practical applications

The linkage between environmental justice language and screening tools is not uncommon. The EPA created EJScreen, and other mapping tools, to comply with an executive order from President Clinton in 1994 to “assess the potential for disproportionate environmental impacts” across the country. Massachusetts also has its own environmental justice tool, directly linked to the existing policies, in order to “enhance inclusive community planning for environmental justice.”

Other non-governmental nonprofits, like Just Zero, borrow definitions from various states for their own work. For example, Executive Director Kirstie Pecci recently used New Jersey’s legislation in a report by the organization.

“The gold standard is shifting and continues to shift,” Pecci said, “but where we can expect corporations to do better is to be honest about why these facilities are located where they’re located, and how far-flung the negative impacts from these facilities are.”

Industries, including the waste sector, often use these tools for their own reporting. For spatial analysis, these companies typically use the federal EJScreen tool, though other options more specific to geography are available. The tools also use varying degrees of language for how communities are named.

"Beyond the differences in language for the targeted population, these tools also differ in degrees of sensitivity and constraints. There are a lot of tools right now that can be used together to provide a more holistic picture and a way to properly identify environmental justice communities. The issue is, those tools are often being used in isolation, and they’re being used against one another,” said Chan.

In addition to releasing more detailed data, Karmel sees more ways for the waste industry to step up to the plate and remedy the differences in language — at least within the industry itself. Analogous to how certain legislation like New Jersey’s is seen as a model bill, Karmel sees room for waste sector players to create something similar.

“There’s a role for an industry group to propose a model legislation in the waste industry,” said Karmel. “This would certainly be a way to standardize and align with industry best practices.”

At the federal level, proposed bills such as the Environmental Justice for All Act that was introduced in March 2021 have sought to establish environmental justice requirements, including for federal agencies to produce community impact reports. Though no explicit move has been made to standardize both the term and definition used to address targeted populations.

The language around how environmental justice communities are named and defined will continue to evolve, though Chan notes that this may not always be beneficial for the communities themselves.

“By defining a term you cabined it instead of addressing the breadth of what makes an environmental justice community,” Chan explained. “These very clear thresholds are ultimately very arbitrary, and don’t capture the nuance of what makes an environmental justice community.”

Karmel sees many ways in which environmental justice definition will continue to play out in legal discussions.

“Do we want to give the same definition of environmental justice communities under an eligibility scenario and a grant or incentive program? Or do we want to change it so that it aligns with the disproportionate burden subset?” he said. “What are the equities and balances of doing that? These are really difficult questions that need to be struggled with.”