Landfill operators are monitoring the progress of a federal bill meant to set a deadline for the U.S. EPA to designate certain PFAS as hazardous substances and establish PFAS drinking water standards. Some waste professionals see the PFAS Action Act as a possible signal that long-expected regulations could finally be on the horizon. The bill passed the House last week.

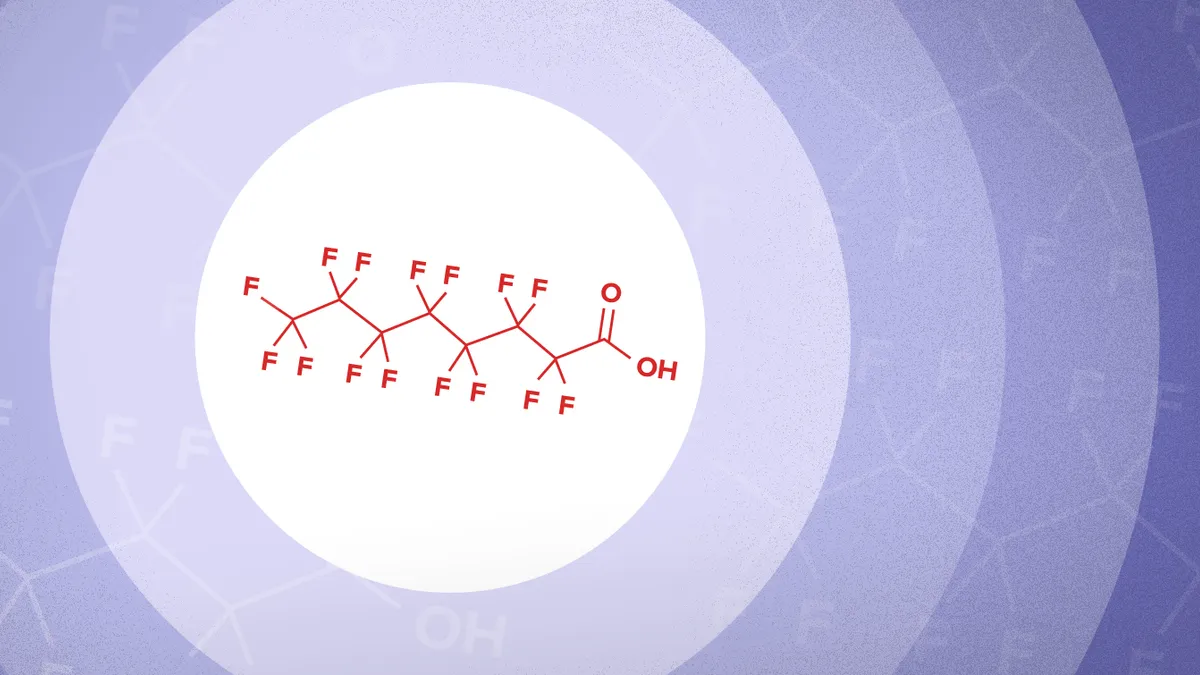

Landfill operators are closely monitoring any federal bills that could give them more guidance on how to manage per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in their facilities. Some see the PFAS Action Act as a sign that a bipartisan bill could potentially bring some clarity and help them fold PFAS management into their business models.

States have already begun passing their own legislation to regulate PFAS in various ways, and some lawmakers have urged the EPA to speed up its regulatory process to avoid a “patchwork of regulations” they say could create confusion or uneven environmental protections.

Although landfill operators have predicted that the U.S. EPA would eventually designate some PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances and set enforceable limits for them in the Safe Drinking Water Act, the PFAS Action Act aims to speed up that process. The bill would give the EPA one year to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances and two years to establish a national drinking water standard for PFOA and PFOS. It would label those chemicals as hazardous air pollutants within 180 days.

"This is Congress stepping in to tell the EPA, 'You have a statute that requires you to look at dangerous chemicals, but you have not done that for many years, and now is the time,'" said Emily Lamond, partner in the environmental law department of Cole Schotz, who monitors PFAS legislation.

According to the bill, the EPA would also have five years to determine whether to list other PFAS beyond PFOA and PFOS as harzardous substances — a group that includes hundreds of other chemicals under the PFAS umbrella. The bill also would also provide $200 million annually each fiscal year from 2022 to 2026 for PFAS-related wastewater treatment, require the agency to set industrial discharge limits and place a moratorium on products containing new PFAS.

Supporters of the bill include the Environmental Working Group, which says the bill sets necessary timelines for reducing and regulating PFAS in the environment. "We need deadlines to ensure that the EPA will take the steps [needed] to reduce PFAS releases into our air, land and water, to filter PFAS out of tap water and to clean up legacy PFAS pollution," said Scott Faber, EWG’s senior vice president for government affairs, in a news release.

The legislation is one of a handful of federal PFAS bills that have been introduced or reintroduced this year, but few have passed. A similar bill last year passed the House with bipartisan support, but then-president Donald Trump said he would veto it if it made it to his desk. Lamond said the bill may have a better chance of passing because of rising interest from the Biden administration to target PFAS issues, in addition to more states passing their own legislation in the absence of federal regulations.

David Biderman, CEO of the Solid Waste Association of North America, said it’s also notable to see Democrats and Republicans work together on such bills. Michigan Reps. Debbie Dingell, a Democrat, and Fred Upton, a Republican, are cosponsors of the PFAS Action Act. "Members in both parties may want to deliver an environmental 'win' before the November 2022 midterm elections," Biderman said.

The association has not taken a position on the bill, but SWANA is monitoring its path through Congress, he said. Landfill operators have a vested interest in following PFAS legislation because of the possible legal and financial implications for how they handle PFAS at their facilities in the future. Landfills do not generate PFAS on their own, but operators still must manage the chemicals because they appear in materials entering the waste stream.

The PFAS Action Act would also require the EPA to create standards to prevent the chemicals from being emitted into the air when burned. Those provisions were once part of a separate bill, Michigan Rep. Andy Levin’s PFAS Safe Disposal Act, but it was recently folded into the larger PFAS Action Act.

Several states have already advanced their own incineration bans, most recently Illinois, which is poised to sign a bill prohibiting the "disposal by incineration" of PFAS-containing materials. State Sen. Christopher Belt, who sponsored the bill, said it would prevent a local waste incinerator from incinerating firefighting foams, a product that often contains PFAS. However, some incinerator operators say their services are one of the few solutions effective enough to break down PFAS.

Recent interim guidance from the EPA for disposing of or destroying certain PFAS substances lists several methods in order of "lower uncertainty to higher uncertainty" in terms of potential environmental impacts. Thermal treatments, such as commercial incinerators and hazardous waste combustors, are listed as having the greatest uncertainty. Meanwhile, methods such as injecting liquid PFAS into deep wells or storing PFAS in hazardous waste landfills and solid waste landfills, are listed as having less environmental uncertainty.

During a WasteExpo panel in June, Dan Jameson, vice president of government and regulatory affairs at Republic Services, said landfill operators are seeking clarity on how to handle future air emission standards for PFAS and what role incineration methods might play, but various proposed bills have not provided many clues. "Can you incinerate it? One bill says you can, while another may say just the opposite. So everyone is really trying to figure out what is going to be the final play," he said.

Several landfill operators have said that even if they aren’t quite sure how to prepare for future PFAS regulations, such regulations are undoubtedly on their way. However, future regulations could represent a business opportunity to manage PFAS-containing materials while awaiting evolution of the technology meant to destroy the chemicals.

“We do look at PFAS as being a cost impact to us, but we look at it as a much bigger opportunity for us than a cost impact,” said Waste Management CEO Jim Fish during his company’s quarterly earnings call Tuesday. Fish made a similar point at WasteExpo’s Investor Summit in June when he mentioned that the company could earn "somewhere in the neighborhood of $5 billion-ish" from PFAS management in an overall market of about $20 billion, depending on the regulatory outcome. He compared the possibility to residual business opportunity from coal combustion.

At a SWANA landfill summit in June, Patrick Stanford, general manager for Rochem Americas, said that landfills are currently the best option "and the only solution available in the next 10 to 20 years" until technology for other methods, such as deep well injection, improves. Many landfills already have been designed to prevent hazardous substance pollution with modern liners, leachate collection, gas collection systems and other technology, he said.

Landfill operators have said they are also mulling whether it's preferable to follow one set of federal PFAS guidelines or a collection of different state laws in the states where they operate.

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham filed a petition with the EPA in June to list PFAS as hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, saying a federal framework will have a better chance at "equally protecting all communities across the U.S." than various state regulations would. “In the absence of a federal framework, states continue to create a patchwork of regulatory standards for PFAS across the U.S. to address these hazardous chemicals. This leads to inequity in public health and environmental protections,” Lujan Grisham said in a press release.

In the meantime, states continue to introduce and pass laws limiting PFAS in water, air emissions and new products. Maine enacted a law in May that bans the use of toxic PFAS compounds in all products by 2030, except in "currently unavoidable" situations. That same month, Vermont passed a similar law banning PFAS in certain consumer products.

They follow developments from 2020, in which New York banned the incineration of firefighting foam with PFAS compounds, and New Jersey enacted stringent new standards for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. Ann Al-Bahish, a partner at the firm Haynes and Boone who tracks PFAS and other public health-related law, said New Jersey is "active on the PFAS front" and is a state to watch for setting other possible PFAS standards in the future.

Keyna Cory, president of Public Affairs Consultants and executive director of the Florida Recycling Partnership, said during a WasteExpo panel that the University of Florida is using its recently awarded $1 million grant from the state to begin studying PFAS impacts and how to contain them in Florida, which could come into play soon as “we're going to definitely start seeing some PFAS legislation starting to move."