Dive Brief:

- The Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) released guidelines last month around food packaging, one of the biggest contamination issues facing organics recyclers. A priority in the guidelines is conveying more specific information about compostability to consumers and end-users.

- The document offers compostable product and packaging manufacturers guidance on labeling and identification strategies. For items that need to be sent to a commercial facility, for example, BPI advises "disclaimer language" including the possibility that such sites may not exist in the nearby area. Printing, embossing, and material coloring are also a focus, along with spacial considerations for smaller items.

- BPI Marketing Director Wendell Simonson said work on the guidelines began before the pandemic, but their release also comes at a key moment. "We think this [the pandemic] could help bring urgency to the massive issue of food scraps heading to landfills and the role that compostable packing and a system of organics collection and processing can play in mitigating it," he said.

Dive Insight:

A number of compost facilities in recent years have moved toward barring food packaging as they wait for consistent guidance to hit the market. Simonson said generating a set of guidelines has been a priority for BPI and members of an internal task force met for several months this year to create the document.

"We know that contamination from non-compostable packaging is among the biggest challenges, if not the biggest, for composters wanting to accept food scraps and, by extension, the packaging that is likely to come with it," Simsonson said. "Poor and inconsistent labeling and identification is a major driver of contamination."

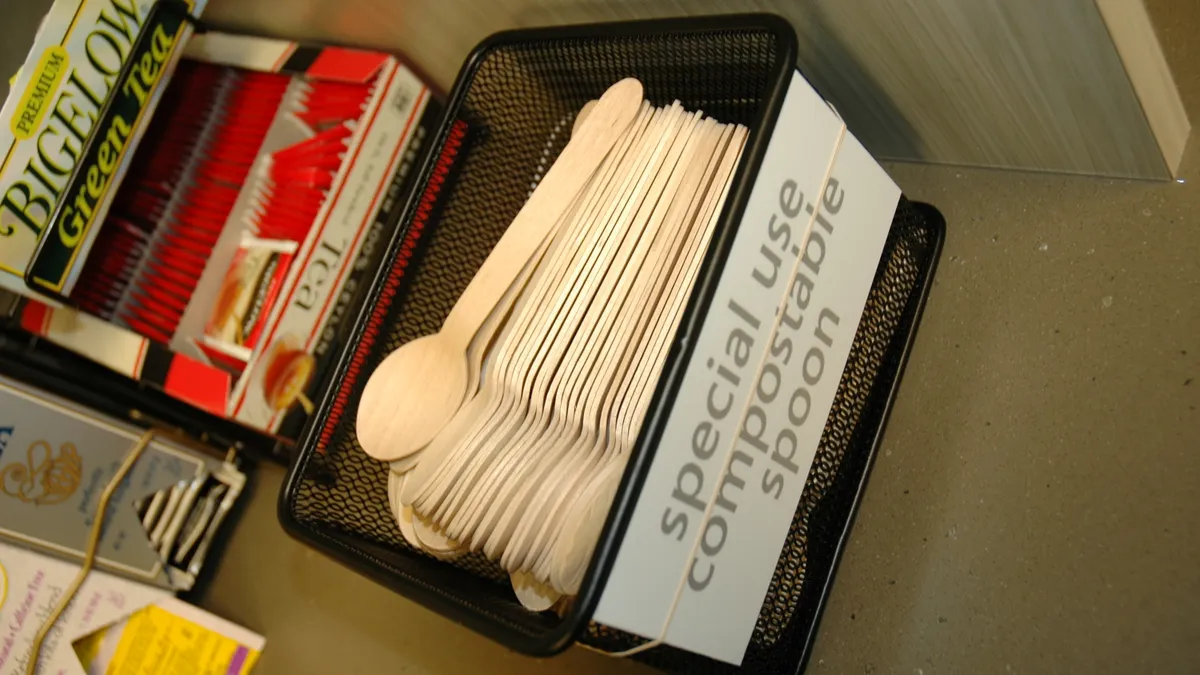

The issue has remained prominent for the organics diversion space — one 2017 BioCycle study by BPI and the Foodservice Packaging Institute (FPI) found less than half of curbside organics programs accepted compostable plastics and packaging. Simonson said items like cutlery and unprinted clear containers are among those posing major challenges, as they offer little visual differentiation from their plastic non-compostable counterparts.

In the guidelines, BPI names multiple considerations for manufacturers including legal and regulatory factors from entities like the Federal Trade Commission. That includes meeting compostable standard certifications, like ASTM D6400. BPI recommends conveying the compostability of a product through specific color schemes — like green and brown striping — as well as the use of the word "compostable" and third-party certification verifying it meets industry standards.

The guidelines acknowledge investments required to implement these strategies "will significantly change the economics for manufacturers and brand owners" with costs likely passed on to customers. BPI recommends a "phased approach" to following the guidelines, beginning with categories less hindered by manufacturing and technology limitations.

BPI invited feedback from multiple players in the organics diversion space, including the U.S. Composting Council and other major composting groups, as well as independent composters, the city of Seattle, and adjacent organizations like FPI and the Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Due to the busy nature of the summer months for the industry, Simonson said it was challenging to get input from composters in particular, which will be a goal for future iterations of the guidelines.

Simonson said state legislation in Washington that went into effect last July also played a role in how BPI crafted the guidelines. H.B. 1569 requires or suggests a number of the guidelines BPI included in the final document.

"That legislation actually calls out 'industry standards' that did not exist before we created this document, so it seemed like the regulators in Washington were inviting the compostable products industry to come up with its own set of industry standards," Simonson said.

BPI anticipates other states will craft similar legislation, Simonson added.

Getting buy-in from the industry is the next major target for BPI, including composters, who have been resistant to accepting food packaging. For example, Rexius – one of Oregon's leading compost facilities – previously stopped accepting food packaging, saying it contributed heavily to contamination. Jack Hoeck, the company's vice president, did not respond to a request for comment about the new guidelines.

Some players have already responded positively. "For me, one of the most exciting possibilities is color tinting to clearly mark certified compostable foodservice items and help composters distinguish them from afar," said Ryan Cooper, waste diversion manager and organics recycling lead for service provider Rubicon.

Cooper noted factors like a preference for clear packaging could pose a market problem, but said he appreciated the range of perspectives contributing to the guidelines and expressed optimism about public reception.

Pandemic-induced constraints have led to an uptick in takeout and delivery, and proponents of compostables hope the guidelines could prove useful given the timing of their release. More broadly, Simonson said BPI wants input from stakeholders working in or adjacent to organics diversion and invited feedback on the organization's recommendations.