The American Chemistry Council (ACC), along with PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, and other big consumer brands, are on a joint mission: to double polyethylene film recycling by 2020 while expanding collection of other hard-to-recycle films.

However the groups have some road blocks to push past as they engage in their "Materials Recovery for the Future" (MRFF) project. One big barrier is that MRFs, already inundated with these lightweight, pliable plastics, can’t handle polyethylene and other flexible films. And the films are a real nightmare when they float into paper streams, turning to sludge as they mix with paper fiber-dissolving solutions.

Even if the contamination problems get fixed, flexible film can present another recycling headache: many of these materials are highly engineered to meet specific manufacturers' needs, which requires mixing resins that are hard to separate, explained Moore Recycling Associates Managing Director Nina Bellucci Butler.

These materials do, however, have redeeming qualities. Production of these flat, lightweight films generates less carbon emissions than other plastics, results in higher product-to-package ratios, and requires fewer trucks to transport.

Additionally, film is actually recyclable and valuable with the proper equipment, said Shari Jackson, director of Film Recycling for the ACC Flexible Film Group. "But for now we have to leverage a unique collection infrastructure, at least until MRFs are retrofitted or built to handle it."

What can be done?

Currently, Jackson's Flexible Film Group is working to set up consolidation points to get the material to the few specialized converters that can handle it—namely grocery stores that collect it send it to distribution centers where it's baled. "Then, converters like Advanced Environmental Recycling Technologies (AERT) and Trex see to it that it’s turned into something interesting and durable, like benches and decking material," said Jackson.

Even a few malls have begun to take ownership of film recycling programs at their sites, and ACC says it will soon have a report on how these early pilots are working out.

The good news is that most flexible film products are made of polyethylene, which can be mixed in one stream—representing a lot of goods that can be tossed in one bin, from plastic bags to wrap-around diapers and feminine products.

The bad news is most people, not even retailers who put out the big collection bins, know this. So the matter of education is another element of what Jackson's Flexible Film Group is working on.

Getting companies on board

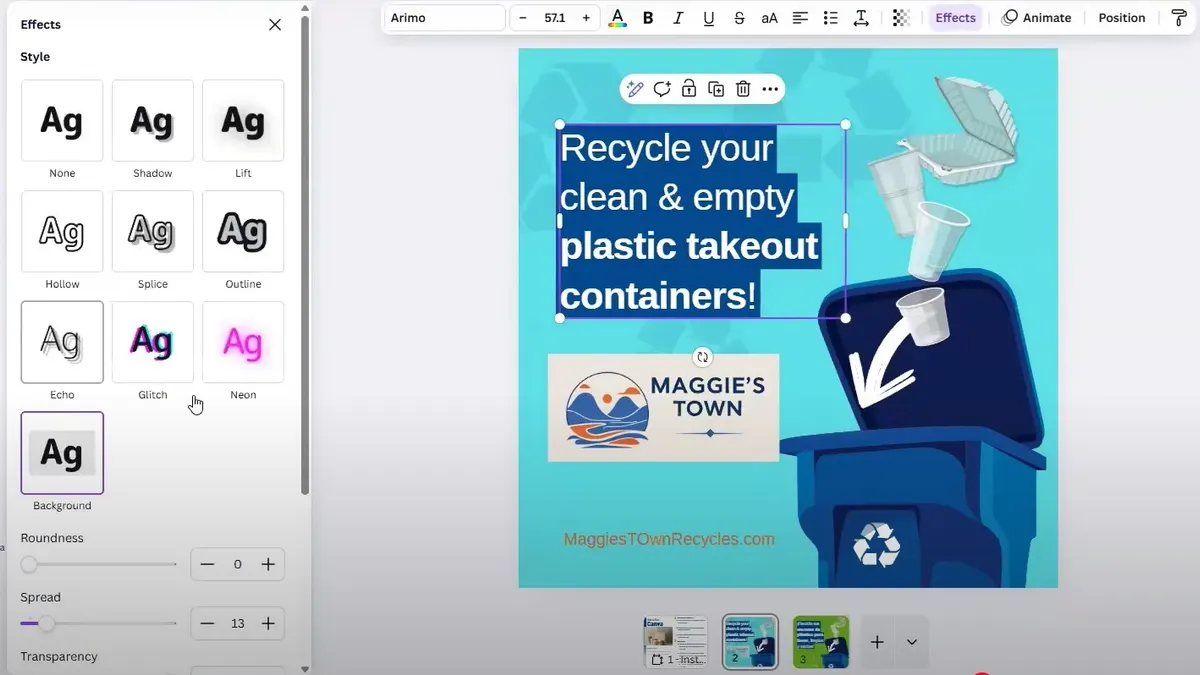

ACC, Trex, Safeway, and the city of Vancouver, WA worked on a public outreach campaign in 2015 in and near Vancouver. 12 Safeway stores there put out well-distinguished polyethylene bins next to trash cans, and customers couldn’t miss them; not only were they huge—holding 40 to 60% more than the ones they replaced—but signs at the registers told them what the bins were for. The end result was a 500% jump in plastic films recovery, from 1.75% to 9%.

But collectors and processors face a daunting task, as different films have different resins and it is impractical to collect by resin type.

"If you try to narrow to one specific resin it may take forever to make a load [film is very lightweight] and you would confuse the public along the way," said Butler. This is where the MRFF partners come in. They are consumer goods brands Amcor Flexibles, Dow Chemical Company, Nestle Purina, Nestle USA, Proctor & Gamble, SC Johnson, Sealed Air Corporation, and PepsiCo.

"Together, we are looking for ways to separate materials and to differentiate that separation," said Brad Rodgers, PepsiCo’s Global Food Packaging R&D director. The company is doing test runs through sorters with their own products to see if they separate from other materials.

"By the end of this summer we plan to put out a public report with initial recommendations for MRFs," he said. "But what would happen today if you put flexible film in a MRF, is it would get separated with paper and contaminate it. We are looking to see if we can do a secondary separation through optical sortation."

Next they will take it up a step, trying to fine-tune the sorters to separate films made from polyethylene, polypropylene, and PET.

Laminated film will be a brain teaser. The multiple layers of materials confuse the optical sorter, which looks for colors and chemical fingerprints each unique to paper, a particular plastic, or other material.

But ferreting out solutions is worth the time and money, figure stakeholders.

"If we have more supply we can expand current applications like composite lumber," said Rodgers. "Then there are brand new possibilities, like use for auto parts, road signs, or other durable products."