The idea that U.S. cities and states could achieve "zero waste" if only people would recycle more has become a common refrain. However the idea that reducing consumption would create less waste to deal with in the first place hasn't quite caught on yet.

Canada is currently celebrating Waste Reduction Week, as it has for the past 15 years, with the support of many government and nonprofit organizations. Across the pond, a U.K. writer has been running a Zero Waste Week since 2008. And while the U.S. has been celebrating America Recycles Day every Nov. 15 for almost 20 years, reduction is not the primary goal. The event’s main call to action is to "reduce my personal waste by recycling" and "buy products made with recycled content."

The federal goal of reducing organic waste 50% by 2030 has sparked some conversations around food consumption, but most other categories of waste tend to get a pass. The unofficial stance in the U.S. seems to be that the use of metal, glass, plastic, paper or any other item can be unlimited as long as it’s possible to collect and recycle those materials cost-effectively. These five charts show that recycling alone may not be enough without more emphasis on reduction and reuse as well.

People may be recycling more, but they're also consuming more

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the national recycling rate of 34.3% is more than five times higher than it was in 1960. At the same time, the average amount of waste per capita has nearly doubled to 4.4 pounds each day. EPA data shows this is down from a high of 4.74 pounds in 2000 and 2006. Yet data from the Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF) indicates the true number may be closer to 6 pounds per day and the national recycling rate could be lower than previously thought.

Even for a person with conservative consumption habits these numbers can add up quickly, as shown this month by activist Rob Greenfield with his trash suit. Other waste reduction advocates have pointed out that in cities such as New York where recycling rates vary widely between neighborhoods, the amount of waste generated per capita is often the same. One recent study from two Boston University academics found that people may actually be willing to waste more if they have the option to recycle.

It may be time for a culture change

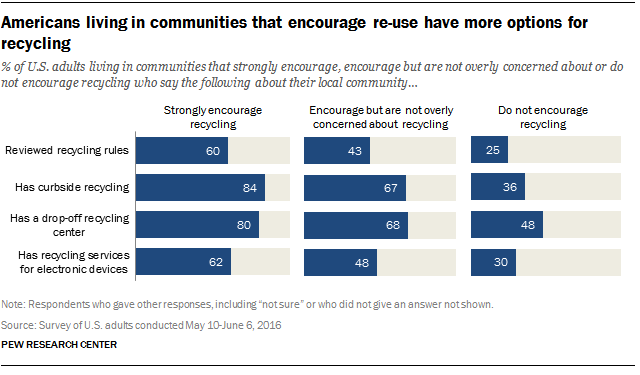

A new survey from the Pew Research Center found that only 28% of U.S. adults feel their community's social norms "strongly encourage" recycling and reuse, 22% said their communities "do not really encourage" it and the rest were in between. Within these groups, Pew found stark differences in understanding and participation which points to the need for more public engagement — whether it be financial, educational or humorous. One U.K. survey showed it could even involve giving residents more information about the recycling process.

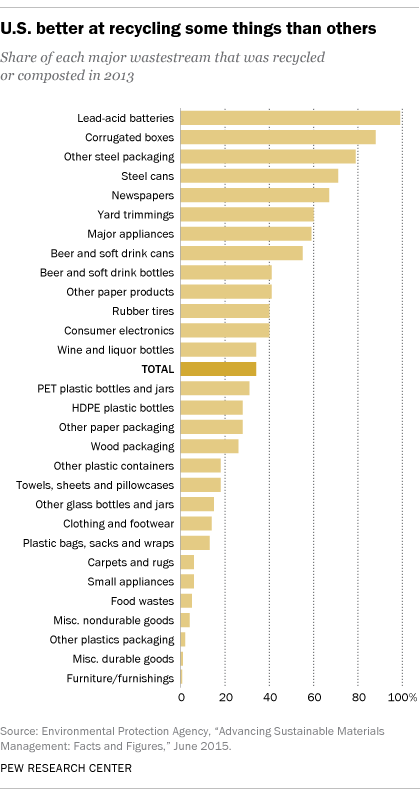

Many of the most successful recycling programs have ample opportunities to donate old items which can be refurbished for reuse. Advocates see this idea as especially promising for textiles, electronics and furniture. This approach could become more important in "zero waste" programs, because as EPA data shows, recycling rates vary greatly when it comes to consumer goods.

All recycling rates are not created equal

The average person does well at recycling specialized, potentially hazardous items such as lead-acid batteries. The steady value of corrugated boxes has also made them a priority for both residential and commercial recyclers. Newspapers and steel are currently experiencing some challenges though have maintained strong recovery rates overall. Diversion rates for most other categories quickly drop off below 60%.

Surveys by numerous industry associations and nonprofits have shown that for common items, this isn’t due lack of opportunity. The vast majority of U.S. residents have access to some form of curbside or drop-off recycling program. At least one study has shown that for big categories such as food waste it may just be because people don’t care enough to change their habits.

Losing control of the single-serving drink trend?

Plastic has come under fire lately for the role some see it playing in marine pollution and other environmental issues. Industry representatives have touted the material's sustainability, but others are skeptical because of the disposable culture they believe it encourages.

Bottles are seen as one of the biggest culprits of this trend and new data from the National Association for PET Container Resources indicates consumption has outpaced collection over the past 20 years. While the reported gross recycling rate was 39.7% in 1995, it was 30.1% in 2015. Lighter material is one key factor in this change, but a spike in the sales of bottled water and other single-serving drinks has also played a role.

We're not running out of space — yet

The path toward zero waste in the U.S. is still unclear. Landfills have hundreds of years of capacity which makes it difficult to justify the higher costs of other disposal methods. Waste-to-energy facilities are often more expensive and not widespread in many parts of the country. Even when the economics do work out for facilities to process recyclables or organic materials, it's still common to see community opposition to waste-related infrastructure.

With the U.S. population projected to reach approximately 417 million people by 2060 — not to mention any other surprises the future may hold — new solutions will be needed. Reduction may not be as easy to explain as recycling, but it’s something the waste industry may be hearing more about soon.